All the land is abuzz about hobbits for one reason or another. There is, of course, the upcoming film duology from Peter Jackson which is reputedly inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien’s books. And then there is the ongoing controversial discovery of Hobbit-little people in Indonesia (current scientific theory seems to favor the argument that they were indeed a legitimate species). And now word is leaking out about upcoming books that will share new insights on Tolkien’s little children’s story.

The Hobbit has long been seen as a diversion for Tolkien from his more serious literary experiments; only since the publication of The History of The Hobbit has it been possible to argue that The Hobbit represents a transformational stage in Tolkien’s myth-making. Although conceived for his children, the tale could not help but borrow from the evolving “Silmarillion” mythology. It also appears that the story introduced elements which only later were fully realized in the legend of Numenor: an ancient kingdom of men destroyed by evil (Dale), a line of kings that survives great disaster (Girion’s descendants), the restoration of a rightful king (Bard), a ship-making civilization that once fielded great armies (Lake-town); and so on.

The main sequence of creation for Middle-earth’s primary elements thus becomes “Quenta Silmarillion” (Valinor, Tol Eressëa, Beleriand, the Eldar and Avari); The Hobbit (Hobbits, Rivendell, Anduin and Wilderland, Mirkwood, Lake-town and Dale, Erebor and the Iron Mountains, the Necromancer’s fortress in Mirkwood, the Wood-elves of Mirkwood and their southern kin in Dorwinion); “The Fall of Numenor” (Numenor); and finally The Lord of the Rings. Each work represents a stage in creativity that drew upon and enlarged the previous stages, and this truly only became clear with The History of The Hobbit.

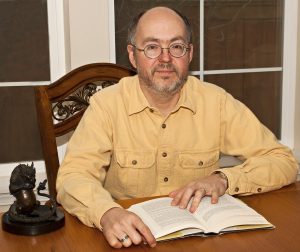

John Rateliff, author of The History of The Hobbit, agreed to answer a few questions about his work and as you’ll see below he has been busy producing some of those new insights. I met John a few years ago at a MERPCon (now named Tolkien Moot) in Spokane, WA. I knew him by reputation as I had long waited for The History of The Hobbit. I had only just barely had time to read it going in to the convention, so I shied away from asking John any of the hard questions I had swirling around in my head. I wanted to be able to read the book(s) again to make sure I understood the material.

We were doing a panel together at MERPCon and John took a question to which he offered what he apparently thought was an incomplete answer. Perhaps he was being courteous. He turned to me, unaware that I had so far only read his HOBBIT history once, and said, “What do you think?” All I could think of to say was, “Dude – I’m still learning from YOU!”

The truth is, I’m STILL learning from John Rateliff – and Christopher Tolkien, and Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull, and Janet Croft, and all the other Tolkien scholars. This is not a topic one masters in a summer or a decade. It requires a lifelong commitment to love of learning and sharing and exploring. J.R.R. Tolkien wasn’t simply a writer or a philologist. He was an incubator. He found ideas that had been left strewn across the English language in odd words and old stories and he grew them into morphic concepts that continue to evolve today.

MM: It has been four years since The History of The Hobbit, Part 1: Mr. Baggins was published. Do you feel the book has had much impact on the study of Tolkien’s works? If so, where do you feel you most succeeded? If not, what do you feel is most being overlooked (in terms of the material you were able to bring to light for the first time)?

JDR: I do feel that the books have helped The Hobbit be taken more seriously in its own right, and on its own merits, than had previously been the case. There had grown up a tendency to think of it as just ‘a charming prelude’ to The Lord of the Rings;, and define it entirely as a lesser work preparing the way for Tolkien’s masterpiece. I think my edition offered a good case for appreciating it as a major work in its own right. If Tolkien had published only The Hobbit, he’d still have earned an honored place in literary history alongside Grahame and Lofting et al.

The part that interested people most was, quite naturally, the 1960 Hobbit.

Most overlooked? I suppose that would be my conclusion from long study of the Plot Notes and outlines that the original ‘battle of five armies’ would have taken place in the vale of Anduin and might well have not involved any dwarves at all. I considered that a pretty startling revelation, and was surprised that no one made much of it.

My personal favorite that so far as I know passed entirely without comment was my proffered solution to the longstanding puzzle of why Tolkien removed the tomato from Bilbo’s larder in later edition of the books but not (say) potatoes and tobacco from LotR.

Astute readers may notice the odd year given for an edition of The Hobbit: 1960. This was in fact an unfinished revision Tolkien began in that year, which better represents how he would have changed The Hobbit during the 1960s had he not been persuaded to leave it as close to its earlier form as possible. The History of The Hobbit includes a section devoted to this ill-fated revision of the beloved story.

(Kenneth) Grahame wrote The Wind in the Willows and The Reluctant Dragon, both of which were made into Disney films. Hugh Lofting wrote the Doctor Doolittle books among others, including the 1930 young adult book The Twilight of Magic where a witch (Scragga the Applewoman) gives a magical whispering shell to two children, Giles and Anne, promising that if they present it to the person who can most use it they will find the fortune they need to save their family from financial ruin. –MM

MM: How do you think Tolkien criticism has been impacted by the connections you made between The Hobbit and The Silmarillion? Have many people asked you about how these connections shaped the story?

JDR: I think I’ve started the wheels turning, but it’ll take a while before the consensus comes round. I’ve noticed this is the sticking point for many, who seem baffled and a little indignant that I’m offering a new interpretation here, based on what seems to me the overwhelming evidence in the manuscript itself. As a larger issue, I think this offers a good test case of what Tolkien scholars can and should do when faced with contradictory statements by Tolkien himself on a point: re-examine and scrutinize all the evidence, including the context in which his statements occur, and see if all or most of the evidence can be assembled into a coherent, convincing picture.

As it so happens, I’ve just finished an essay on this very point, called “A Fragment, Detached: The Hobbit and The Silmarillion“, for the French Tolkien journal Tolkiendil; it will also form the basis of my paper on the same topic at next year’s Medievalist Congress at Kalamazoo. So we’ll see what the Tolkien scholars there make of my argument.

I might add that one of the letters I treasure that I got after the book was published was from my friend Franklin Chestnut, who’d introduced me to many of what became my favorite fantasy writers (not least John Bellairs), saying that I’d convinced him on this point. We all have one or two people whose opinion or judgment we really trust, so that meant a lot to me.

Franklin Chestnut passed away on October 3, 2010. John wrote a touching memorial for his friend on his blog. –MM

MM: You took on The History of The Hobbit after Taum Santoski died in 1991. You and your wife Janice were very close to him. You recently commemorated Taum on your blog with many quotes. How much influence would you say Taum had on the final book? Does he get enough credit from other scholars? How closely did your own deductions and intuitions agree with Taum’s?

JDR: Yes, Taum was my best friend. Janice and I saw him almost daily during the two years of his terminal illness. He had a huge impact on the book, not least in that without him the project would never have gotten off the ground. I’d say his influence is strongest in the arrangement and sequencing of the materials. For example, he was the first to identify two stray leaves in the Marquette collection as belonging to an earlier manuscript of the first chapter, and when Christopher Tolkien published a facsimile of the ‘only page preserved’ from the original draft (in his Foreword to the 50th anniversary edition of The Hobbit), Taum recognized it as once as cognate with the two leaves at Marquette; from this we were able to reconstruct “The Pryftan Fragment”. He also figured out the sequence between The First Typescript and The Second Typescript, which everybody had backwards before that point, and the importance of “The Bladorthin Typescript”. Pretty important stuff for understanding the stages in which the story was written and revised.

But our approaches were radically different. The original draft of Taum’s edition, which I’ve deposited at Marquette, has very little annotation and almost no commentary. Had he lived to finish it, his edition would have been much shorter, presenting a text that incorporated all changes made to the manuscript with only a few brief text notes; the commentary would have been restricted to glosses of names in Tolkien’s invented languages, Tolkienian linguistics being Taum’s vocation.

Enough credit: I don’t think so, but then it’s difficult for me to judge. I know I often check the indexes of new books on Tolkien when they arrive to see if Taum is mentioned, and am almost invariably disappointed. I’d considered putting his name on the title page (“by John D. Rateliff, with Taum Santoski”) but eventually decided that it’d be confusing to have Tolkien and myself and Taum all there, so I tried to convey his contribution in the Acknowledgments instead. I wish he’d written up more than he only left in notes, so more could have been published (e.g., his piece comparing The History of Middle-earth with other posthumous publication projects, which was quite interesting but exists only in notes and an audiotape of an oral presentation). Hence my publishing those theoretical notes on my blog, to share them even in their unfinished state.

MM: In 2007 you called for Errata for the book. Did anyone uncover something significant enough that citations of earlier printings might have been discredited or weakened? If someone owns a First Printing of The History of The Hobbit, should they be concerned that something huge slipped by unnoticed?

JDR: Most of the errata involved typos and small factual errors—cringeworthy enough in an author like myself, who’s worked as a professional editor and proofreader in the past, but not particularly significant. For example, at one point I absent-mindedly mixed up Langland and Gower in a passing reference. Gah! I assume any English major who reads that line sees the gaff and moves on. More seriously, I was misinformed about the whereabouts of one manuscript collection (of Denham’s tracts); this and similar slips are being corrected in the new revised one-volume edition, just out from HarperCollins.

So no, nothing that invalidates the original edition; just some typos I wish weren’t there and new things I would have added in if I’d known about them in time.

On page 147 of The History of The Hobbit John included “Gower’s Visions of Piers Plowman” in a list of medieval works with which J.R.R. Tolkien would have been familiar. Tom Shippey pointed out in his review of the book for Volume 5 of Tolkien Studies that scholars now generally believe William Langland wrote “William’s Vision of Piers Plowman”, an allegorical narrative poem composed in Middle English in the 1300s.

The first appendix in The History of The Hobbit is devoted to Michael A. Denham’s mid-1800s list of names of fairy-creatures from English literature and folklore, in the midst of which the word “hobbit” inexplicably appears. John argues that it may be related to 8 other hob- names (including hobgoblin). –MM

MM: In the book you note numerous connections between Tolkien’s children’s stories and his more serious literary compositions (notably “Quenta Silmarillion”). Do you have a sense of how much his children might have been aware when they were hearing or reading these stories that JRRT was sharing something more with them? How much influence do you think the Tolkien boys had on the shaping of Middle-earth itself as its evolved within The Hobbit?

JDR: That’s a good question that I don’t know the answer to. Certainly bears loom large in The Hobbit, Father Christmas, and Mr. Bliss because all four of Tolkien’s children loved bears and bear-stories. I sometimes wonder if he ever read “Sellic Spell”, his re-creation of the bear’s son story said to have underlain Beowulf, out loud to them. And, if so, what they made of it.

But as to the larger question, Michael Tolkien asserted that many of Tolkien’s works were directly inspired by various of his toys (Roverandom, “Tom Bombadil”, Mr. Bliss) but doesn’t make any claim to have influenced the mythology that I’m aware of, unless you count his sharing his father’s ‘Atlantis complex’ (the dream of the great wave). So, so far as I know, Christopher was the only one of the children interested in The Silmarillion tales, and from quite early on too (there’s a reference somewhere to him hearing “The Fall of Numenor” when it was newly written).

It’s risky to draw firm conclusions with so little evidence, though, esp. given how few letters from JRRT discussing his work we have from the two decades preceding the publication of The Hobbit.

MM: The Hobbit is oft-times criticized for being a “Boy’s Story”. In your research have you found anything where Tolkien wrote something, even if only a brief note or essay, that might have been devised for Priscilla or Edith’s sake? Is it really all just “for boys”?

JDR: So far as The Hobbit goes, I think it’s one of those stories like The Wind in the Willows and The Voyages of Dr. Dolittle that girls can enjoy just as much as boys, even though the cast of all three is pretty much all male.

I don’t know of any work written particularly for Edith or Priscilla, aside from the latter Father Christmas Letters being explicitly crafted with Priscilla’s likes and interests in mind. We do know Edith was the first person he showed The Book of Lost Tales and Smith of Wootton Major to, and he encapsulated what he felt for her in the Beren & Luthien story. And we know Tolkien was deeply concerned in women’s issues, as shown by works as diverse as Eowyn’s story and “The Last Ship” on the one hand and “The Mariner’s Wife” and the “Athrabeth (ah Finrod and Andreth)” on the other. But to what extent any of these were written “for” his wife or daughter I cdn’t say.

MM: There are many puzzling aspects of The Hobbit, such as names of characters, how events were rearranged, use of symbolic creatures and incidents, etc. Do you think of one being more puzzling, more intriguing than the others?

JDR: I find fascinating his attempt to resolve all the calendrical contradictions in the story in the 1960 Hobbit: going round and round between three mutually contradictory ‘facts’ that can’t be reconciled. Elsewhere he was able to affect sweeping changes with the stroke of a pen; why was he so hesitant to do so here? His attempt does prove the truth of his maxim that you have to draw the map first; a sufficiently detailed story, like the kind Tolkien wrote, can’t be made to fit an outside pattern, whether geographical or chronological, after the fact.

The one question I’d most like the answer to myself is whether he really uses the word “Gondobar” in the draft of Bilbo’s final poem in The Hobbit manuscript [HoH.693], or are my eyes just seeing something that’s not there? Someone with better eyesight than mine will have to resolve that one.

MM: The names in the earlier drafts of The Hobbit seem to be less mature than those used in the final drafts of the 1937 Edition. Was Tolkien simply being silly and casual with the early names or do you feel he was operating by a different set of equally rigid rules?

JDR: Actually, I think the original set of names he chose—Bladorthin the wizard, Gandalf the dwarf-leader, Pryftan the dragon, Medwed the werebear—are just as good as the familiar Gandalf the wizard, Thorin, Smaug, and Beorn he wound up with; we’re just familiar with one set of names and not the other. It’s part of the Mooreeffoc effect: seeing The Hobbit as it was when it was first conceived and written, rather than from the retrospect of what all it lead to and the ways those subsequent events change the way we now see the book.

MM: In July 2011 you published “Bilbo’s Clue (clew)” on your blog, revising your interpretation of one of Bilbo’s names for himself. If you had to write the book over again today, do you think it would be substantially different from the current version? If so, what would it take to publish a new edition?

JDR: Well, actually I spent this summer preparing the new edition that’ll be out soon (sometime later this month, I think). I’d prepared a new appendix (Appendix V: The Author’s Copies List) and what I call the Addendum several years back, but they needed a lot of work to see them through the press. Esp. the latter, which represents a few pages of new material by Tolkien, mainly dating from circa 1965-66 (found by Christopher Tolkien in one of his father’s copies of The Hobbit, but too late for me to include in the original printing).

This is a ‘new edition’ in that it adds some new material at the end and fixes errors where I’m aware of them. But it’s not a complete re-write: we weren’t able to re-typeset the whole, so I couldn’t add as much new material as I would have otherwise. For example, information I’d put up on my blog re. a Sixth and Seventh ring of invisibility that could have been among Tolkien’s sources for Bilbo’s ring is referenced in a daggered note referring people to the blog entry, since we weren’t able to squeeze whole new paragraphs into that chapter. A long piece on trolls turning to stone in Grettir’s Saga (which I owe to Marjorie Burns) and in a piece by Helen Buckhurst (which I owe to Doug Anderson) appears in abbreviated form. I’d also have liked to add more acknowledgments than there was room for, to thank all those who sent in errata by name. I was able to add about a page regarding a still-earlier form of Denham’s list. And the whole benefits from Charles Noad’s scrupulous proofing.

Helen Therese McMillan Buckhurst was an Icelandic scholar and friend of J.R.R. Tolkien’s whom he met at Oxford; in 1926 she read a paper, “Icelandic Folklore”, at a meeting of the Viking Society in London. The Viking Society publications are available online. The Helen Buckhurst paper was published in Volume X – Proceedings. Thanks to Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull for the reference. –MM

MM: How much interest do you think the Peter Jackson movies will stir up in your work? Are you seeing any early increase in Hobbit-related research already?

JDR: Oh yes, very much so. In addition to the new edition of my book, which has been planned for several years, there’s Wayne & Christina’s book on Tolkien’s artwork for The Hobbit (really looking forward to that one) and Corey Olsen’s book on everything-you-wanted-to-know-about-The Hobbit.

I’m sure there will be many more over the next three-four years. The more the merrier, sez I.

MM: What does “Sacnoth” (the name of John’s blog, Sacnoth’s Scriptorium) mean? How did you choose that name for your blog?

JDR: In addition to being a Tolkien scholar, I’m also interested in fantasy as a genre. One of my favorite other fantasy writers is Lord Dunsany, whose influence is second only to Tolkien himself (who in turn was greatly influenced by Ld D): I did my dissertation on Dunsany’s work after my original topic (Tolkien’s role in the emergence of fantasy as a modern literary genre) was rejected. And one of Dunsany’s early masterpieces is the story “The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save for Sacnoth”. It’s a quest story, arguably the first ‘sword and sorcery’ story ever written [1907], about an evil wizard who can only be defeated by the magical sword Sacnoth. And Sacnoth can only be forged out of the spine of a dragon named Tharagavverug. And this particular dragon can only die by starvation, so the hero has his work cut out for him (he essentially has to fight the dragon for three days and nights until it starves).

So my use of the name ‘Sacnoth’ is both a glancing allusion to the-pen-and-the-sword (since for years I worked as an editor, mainly of rpgs), and also a reminder of a great writer’s work that doesn’t get nearly the attention it deserves.

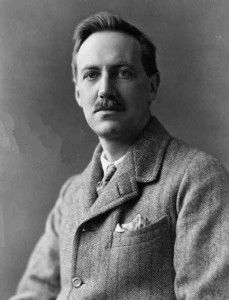

Biographical Note

John D. Rateliff grew up in Arkansas but moved to the state of Wisconsin in 1981 so that he could work with the Tolkien manuscripts at Marquette University. John began his lifelong career in Tolkien scholarship while still in the 9th grade, when he wrote a review of The Hobbit for his school newspaper and commenced to track down every published work from Tolkien that he could find. While attending Southern Arkansas University John succeeded in persuading the university to add a class on Tolkien to its curriculum and he was one of its first students.

Prior to leaving Arkansas, and while at Marquette, John connected with the role-playing game community. John’s research into the literature of J.R.R. Tolkien and Lord Dunsany served as a good foundation for his editorial and creative work with TSR, Inc. (later acquired by Wizards of the Coast, which was subsequently acquired by Hasbro) the company co-founded by Gary Gygax, co-creator of Dungeons and Dragons.

John helped organize the Tolkien collection at Marquette University and he was among several people whom Christopher Tolkien thanked in print for providing assistance with his father’s papers during the production of the 12-volume History of Middle-earth series. John also taught a night-course on Tolkien and fantasy as part of Marquette’s Continuing Education program. His extracurricular activities also include participating in readers groups and organizing conferences. Dr. John Rateliff has published Tolkien research and related essays in various journals and collections including Tolkien Studies and Tolkien’s Legendarium. He won the 2009 Mythopoeic Award for Inkling Studies for The History of The Hobbit Part 1: Mr. Baggins.

# # #

Have you read our other interviews with Tolkien scholars?