Q: Are There Two Kinds of Magic in Middle-earth?

155 To Naomi Mitchison (draft)

[A passage from a draft of the above letter, which was not included in the version actually sent.]

Despite the fact that Tolkien never sent the section that follows, many readers believe it is a meaningful discussion of elements in Tolkien’s fiction. However, they ignore a critical end note attached to the paragraph that reads:

Anyway, a difference in the use of ‘magic’ in this story is that it is not to be come by ‘lore’ or spells; but is in an inherent power not possessed or attainable by Men as such. Aragorn’s ‘healing’ might be regarded as ‘magical’, or at least a blend of magic with pharmacy and ‘hypnotic’ processes. But it is (in theory) reported by hobbits who have very little notions of philosophy and science; while A. is not a pure ‘Man’, but at long remove one of the ‘children of Luthien’2.

If you read Note No. 155/2, you will find:

Alongside the final paragraph, Tolkien has written: ‘But the Númenóreans used “spells” in making swords?’

He did not send this text to Naomi Mitchison because it contradicted what was in the book. So the idea that Men could not use magic is completely discredited. Among the other examples of magic-using men that we can easily point to are:

- Beorn the skin-changer, whom Tolkien described as “a bit of a magician” in Letter No. 144 (also composed for Naomi Mitcheson)

- Aragorn’s healing power as well as his enchantment over the Morgul-blade

- Queen Beruthiel’s sorcery

- The magic powers of the Nazgul themselves (enhanced or conferred by their Rings)

- The Hill-folk of Rhudaur who used sorcery

And now let us address the other oft-cited source of information: Letter No. 131. This is the letter that Tolkien composed for Milton Waldman, who was then publisher of Collins (now part of HarperCollins, as is George Allen & Unwin, who were the original publishers of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings). In this Letter Tolkien meant to lay out and explain many things, for he hoped that Waldman would find a way to publish The Lord of the Rings, which Tolkien had angrily retracted from George Allen & Unwin when they declined to publish that book along with The Silmarillion. Tolkien introduces three primary concepts early on in the letter: Fall, Mortality, and the Machine.

…Anyway all this stuff* is mainly concerned with Fall, Mortality, and the Machine. With Fall inevitably, and that motive occurs in several modes. With Mortality, especially as it affects art and the creative (or as I should say, sub-creative) desire which seems to have no biological function, and to be apart from the satisfactions of plain ordinary biological life, with which, in our world, it is indeed usually at strife. This desire is at once wedded to a passionate love of the real primary world, and hence filled with the sense of mortality, and yet unsatisfied by it. It has various opportunities of ‘Fall’. It may become possessive, clinging to the things made as ‘its own’, the sub-creator wishes to be the Lord and God of his private creation. He will rebel against the laws of the Creator – especially against mortality. Both of these (alone or together) will lead to the desire for Power, for making the will more quickly effective, – and so to the Machine (or Magic). By the last I intend all use of external plans or devices (apparatus) instead of development of the inherent inner powers or talents — or even the use of these talents with the corrupted motive of dominating: bulldozing the real world, or coercing other wills. The Machine is our more obvious modern form though more closely related to Magic than is usually recognised.

Some readers mistakenly identify the Machine with Magic because of Tolkien’s sentence here, but they do not take into account what precedes the use of these words: the rebellion that leads to a desire for Power and “for making the will more quickly effective”. In the following paragraph Tolkien writes:

I have not used ‘magic’ consistently, and indeed the Elven-queen Galadriel is obliged to remonstrate with the Hobbits on their confused use of the word both for the devices and operations of the Enemy, and for those of the Elves. I have not, because there is not a word for the latter (since all human stories have suffered the same confusion). But the Elves are there (in my tales) to demonstrate the difference. Their ‘magic’ is Art, delivered from many of its human limitations: more effortless, more quick, more complete (product, and vision in unflawed correspondence). And its object is Art not Power, sub-creation not domination and tyrannous re-forming of Creation. The ‘Elves’ are ‘immortal’, at least as far as this world goes: and hence are concerned rather with the griefs and burdens of deathlessness in time and change, than with death. The Enemy in successive forms is always ‘naturally’ concerned with sheer Domination, and so the Lord of magic and machines; but the problem: that this frightful evil can and does arise from an apparently good root, the desire to benefit the world and others* — speedily and according to the benefactor’s own plans — is a recurrent motive.

The distinctions that Tolkien draws here are between motivations and goals: for “sub-creation” on the part of the Elves and for “Domination” for the Enemy. He labels the activities of the Elves Art and the activities of the Enemy the Machine or magic. But these activities are all derived from the same sources: the strength of the spirits of the beings who are engaged in the activities.

Some readers cleverly divide the natural abilities of Tolkien’s characters according to their races: Ainur (Valar and Maiar) have the greatest power and sometimes their activities are called “Ainurian magic”, “Ainurian power”, “Maiaran magic”, etc. But the magic or power is simply the will of the being expressed according to its native strength, which is greater than that of an Elf, Dwarf, or Man (or Hobbit).

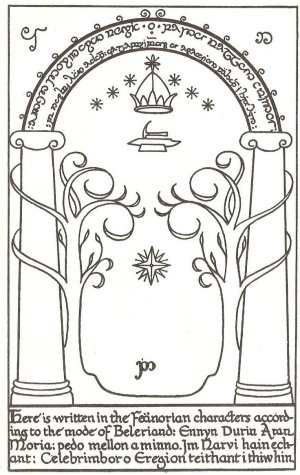

We see the Elves as having the greatest power after the Maiar, if only because Feanor and his grand-son Celebrimbor made the greatest artifacts of the Elves, the Silmarils and the three Rings of the Elves. Of course, Elves display magic all over the place, and Tolkien casually describes their use of spells and sorcery, especially in the older tales that led to The Silmarillion (see Luthien and Finrod for quite explicit uses of these words with their actions).

Dwarves create magical armor, weapons, toys, lights, and other artifacts but none seem to equal the artifacts of the Elves. I am not sure that means Elves were legitimately more powerful than Dwarves; Tolkien seems to provide no basis for comparison in terms of innate abilities. The Elves and Dwarves learned much from each other, but they had different social and cultural priorities.

Men displayed less power than either Elves or Dwarves, although the Númenóreans did create monumental structures such as Orthanc and the walls of Minas Tirith, which seemed to possess magic-like properties. The Art of the Númenóreans may only have been a technology elevated to a status comparable with the Art of the Elves in terms of craftsmanship; Tolkien doesn’t really say. But we do know that the barrow-blades were dangerous to the Nazgul and other creatures who served Sauron (the Orcs who seized Merry and Pippin did not take the swords with them). So Númenórean magic should not be lightly dismissed. In the Prologue Tolkien only said that “Hobbits have never, in fact, studied magic of any kind”; he did not say they possessed no magic. In The Hobbit Tolkien wrote “there is little or no magic about them, except the ordinary everyday sort which helps them to disappear quietly and quickly …” This gift, of course, is dismissed as a non-magical talent in The Lord of the Rings, but Frodo’s spirit grows (becomes stronger) as a result of his long battle with the Ring. In Letter No. 246 Tolkien wrote:

Frodo had become a considerable person, but of a special kind: in spiritual enlargement rather than in increase of physical or mental power; his will was much stronger than it had been, but so far it had been exercised in resisting not using the Ring and with the object of destroying it. He needed time, much time, before he could control the Ring or (which in such a case is the same) before it could control him; before his will and arrogance could grow to a stature in which he could dominate other major hostile wills. Even so for a long time his acts and commands would still have to seem ‘good’ to him, to be for the benefit of others beside himself.

Tolkien here suggests that Frodo could indeed have learned to use the Ring to dominate the wills of other beings, had he been left free to do so without interference from Sauron and the Nazgul. This is an important passage, for though it makes it plain that the Ring would have conquered Frodo (as it did at the last moment), in such a conquered state he could have still used the Ring, wielding its power, even though he would no longer be good. But Frodo’s “spiritual enlargement” is also important, for this is how Tolkien explains the difference between the two occasions were Sam was given “other vision”. The first occasion slips past many readers. It is the moment where Frodo strikes his bargain with Gollum to lead the Hobbits into Mordor:

For a moment it appeared to Sam that his master had grown and Gollum had shrunk: a tall stern shadow, a mighty lord who hid his brightness in grey cloud, and at his feet a little whining dog. Yet the two were in some way akin and not alien: they could reach one another’s minds. Gollum raised himself and began pawing at Frodo, fawning at his knees.

The second passage is when Gollum attempts to seize the Ring on the slope of Orodruin, before Frodo enters the Sammath Naur:

Then suddenly, as before under the eaves of the Emyn Muil, Sam saw these two rivals with other vision. A crouching shape, scarcely more than the shadow of a living thing, a creature now wholly ruined and defeated, yet filled with a hideous lust and rage; and before it stood stern, untouchable now by pity, a figure robed in white, but at its breast it held a wheel of fire….

Despite his spiritual enlargement Frodo could not ultimately overpower the will of the Ring, which conquered him at the last moment. But Frodo’s struggle with the Ring — and his spiritual growth — illustrate how even Hobbits possessed that native strength, that spiritual gift, in some measure, which the Ainur, Elves, Dwarves, and Men used as Art or magic.

It was all the same thing, expressed according the stature of the being wielding it, and shaped by the purpose and goal of the wielder: either to “sub-create” or to “dominate”, and/or perhaps also to resist.

Hence, there is simply no basis for saying there was more than one kind or type of magic in Middle-earth. Tolkien’s Elves were confused by the Hobbits’ use of the word to describe what was achieved, which to Elven thinking was different for them than it was for Morgoth or Sauron. And yet the Elven philosophy is not necessarily the author’s philosophy. If it were critical for the reader to understand that there were indeed two or more distinct kinds of power or magic in Middle-earth then Tolkien would have said so clearly; and at one point he tried to make that case, but realized that it was too late to make such a distinction.

Instead he had to satisfy himself with distinctions in application and purpose. The Elves simply looked at things from a different point of view. But they were also guilty of Domination, for they had made the Rings of Power to extend their enjoyment of Middle-earth, and to ensure that they remained its dominant civilization; and they used the Rings even after Sauron’s betrayal, although they should have realized by then just how evil the Rings were. To the Elves the Three were “unsullied” because Sauron had no part in their making, and yet they were still manifestations of the Elves’ second fall, and in the end they could not escape the fate of all the Rings of Power. The Three failed when the One Ring was destroyed. That is because their strengths, though coming from different beings, were of a similar or singular nature.

# # #

Have you read our other Tolkien and Middle-earth Questions and Answers articles?

Yeah discussion about magic!! 🙂 Well there is actually many examples of magic in Lotr, even Barrow Wights are capable of magic to some degree, ”dreadful spells of the Barrow Wights of which whispered tales spoke” them chanting those awesome sounding words in that strange ritual they subjected the hobbits, this green light (and light in the very eyes of those undead things), not to mention Dragon-spell that appears to be affecting mind in many ways bordering on mind control with Glaurung even wiping memories, magically induced amnesia 🙂 (hmmm Dark Lords too appear to be able to dominate minds directly, mind control over Orcs for example, elves appear to be able to master animals, their ”way with good beasts” seems like this soothing with voice and mastering a horse in seconds is more ‘magical’ than mundane skills with animals). There are enchantments of elves like those enchantments used by Wood Elves of Mirkwood that seemed to ward off evil creatures, this good power lingering in such spots like sites of elven feasts that spiders didn’t like, them having fires and lights suddenly lit or put out, the enchanted hills around Gondolin, warriors of Nargothrond fighting with ”stealth and ambush, with WIZARDRY and venomed dart”, Songs of Power (though I’m still wondering what are they capable of, elves seem to be able to make some sort of illusions through their singing but would they be able to affect the physical reality by it? Are the Songs of Power something higher than other songs used by elvish minstrels with that kind of power?), various men or elves or even dwarves (like Balin in The Hobbit, who seemed to understand language of birds including crows, though not of thrushes) talking with animals, Beorn seems to be able to do other things besides that and his shapeshifting (he appears to be able do some illusions too his house is sometimes strange giving different sensations, or breeding magical or highly unusual creatures, animals serving him and bees larger than thumb, can you imagine bees of THAT SIZE!? How big bee-hives they must make hehe), there are also those candles of corpses in Dead Marshes that seems to hypnotize people both Sam and Frodo felt it’s influence and Gollum warns them to not look into them (I wonder whether them being such resistant to any magic-like forces, Rings of Power, enchanted morgul knives is also what prevents them from falling completely to this pull and what would have happened if whole Fellowship would went that way, would Men be more affected? Dwarves too seems to be more ‘magic-resistant’ :)) and what about Thorin’s company using spells on the hidden troll hoard ‘great many spells’ were they real spells with some kind of power, there are also some hints about ‘runes of power upon the door’, and runic spells on eastern gate of Moria (now destroyed) and all the other dwarf-gates, like that back-door to Erebor that was virtually indestructible other gates would be similar too maybe (and that would explain why Sauron couldn’t get to Moria when they shut the gates in war with elves in Eregion hehe), their crafting also have many properties, Narsil was made by a dwarf after all and it is said to shine with the light of moon and sun, reddish at day and cold white at night, blades even if polished wouldn’t shine so, nor would they so easily cut steels helmet in half hehe works of Telchar are really super sharp, there would be probably some technological developments well some sort of simple machinery MUST HAVE BEEN used by dwarves just as hobbits would use such simple machinery like watermill or handloom, or forge bellow and dwarves would be most likely much more advanced, as Gadnalf tells tehre is no smith’s forge that would even heated the One Ring and NOT EVEN FURNACES AND ANVILS OF THE DWARVES would harm it, implying they are most advanced though probably if any great workshops of Noldor remain they could be possibly be similar. Well what do you think about all this?