In 1977 I walked into a bookstore and asked when The Silmarillion would be released. The manager told me it was coming out in 3 weeks but if I did not put my name on a waiting list he would not be able to guarantee I would receive a copy on the first day. “750,000 copies were ordered for the first printing,” he told me, “and they are already talking about the second printing.”

Years before I had discovered Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan, John Carter of Mars, Carson Napier of Venus, and many other heroes. His stories were epic, world-spanning, ecosystem-defining sensations for me. And at 14 I stumbled across Warlock of the Witch World by Andre Norton. I devoured these books eagerly, but they were slow to find me. At 15 I shared my frustration with a friend. “Have you read anything by J.R.R. Tolkien?” my friend asked.

That was, I think, a life-changing question. In retrospect I see that it set me on a path that has continued to this day and which will, I hope, continue into the distant future. I devoured The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, and Robert Foster’s handy little Guide to Middle-earth. I envied the entire generation before me who had grown up with these wonderful books. Upon finishing The Silmarillion I wanted more, and my heart sang all day when I first learned that Unfinished Tales of Numenor and Middle-earth was to be published.

And yet, as I found myself reading Unfinished Tales and The History of Middle-earth the horror of what had been done dawned on me, volume-by-volume. J.R.R. Tolkien had NOT written The Silmarillion. He wrote bits and pieces of it, here and there — but his son Christopher made editorial changes and additions — the revelations of which explained many once-puzzling aspects of the books. Through the years I have often turned back to Christopher’s foreword in The Silmarillion where he wrote:

…It became clear to me that to attempt to present, within the covers of a single book the diversity of the materials — to show The Silmarillion as in truth a continuing and evolving creation extending over more than half a century — would in fact lead only to confusion and the submerging of what is essential. I set myself therefore to work out a single text selecting and arranging in such a way as seemed to me to produce the most coherent and internally self-consistent narrative….

A complete consistency (either within the compass of The Silmarillion itself or between The Silmarillion and other published writings of my father’s) is not to be looked for, and could only be achieved, if at all at heavy and needless cost….

He tried to tell us, without explaining all the details, what he had done. Christopher was very honest from the start about the nature of the text. But in 1977 I was too young, too inexperienced, as yet too unread to understand fully the meaning of his confession. I thought the book was the most fantastic thing I had ever read, outside of the Bible itself. All the wonder of Creation, all the hopes and despairs of a fallen people who longed for redemption, who had no hope in their own works and deeds of repairing the harm they had done to themselves, was there to be read and enjoyed and pondered without the burden of fear of retribution for sin.

Over the past 15 years I have discovered many interesting people and places to discuss the works of J.R.R. Tolkien: Compuserve, the News Groups, Suite101, my own forums at Xenite.Org and SF-Fandom, and dozens of other Web forums and mailing lists. There have been long debates, great wars of passion and vehemence, sweeping attempts to analyze and understand what The Silmarillion truly is, what it means, and where it should lead the reader in discovering Tolkien’s secondary creation, his fabled Legendarium. The most grueling tasks were the efforts to document specific passages that were used to create the published Silmarillion.

I have oft joked that you can find the entire text of all the Tolkien books online — because I feel like I have cited them from cover to cover. ‘Twas passion that drove me to such excess — or perhaps an addiction before which I found myself helplessly humbled. One cannot discuss The Silmarillion without feeling something. Perhaps it has so moved its readership to the extremes of love and hate because the work represents the passion of two very dedicated men, father and son, who if they did not share the same vision at least shared the same responsibility: to bring The Silmarillion into a final published form. J.R.R. Tolkien made the promise and Christopher Tolkien fulfilled it.

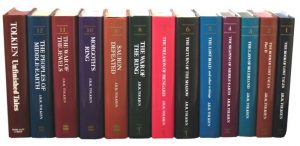

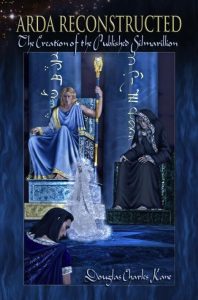

And then Christopher followed up with a full explanation of what had been done, and most of the whys and wherefores are now logged and recorded amid the scattered pages of 13 books. Yet, through all that we have no concise guide or map explaining exactly how the texts were sourced. Christopher left that unenviable task to other hands, other minds. Thus in 2009 Douglas Charles Kane published the first definitive mapping to The Silmarillion and its source texts in Arda Reconstructed.

I feel a certain respect and admiration for anyone who had the temerity and patience to create such a work. Arda Reconstructed has been reviewed by others and if you have not read the book they can tell you sufficient about it to help you decide whether to buy it. But let me point out that Doug Kane went further than to merely document the pattern of selections Christopher made from the sources: he saw deeper patterns and noted them with some commentary throughout Arda Reconstructed.

Not everyone has agreed with his observations, but this is the way of Tolkien readership. I suspect that there are still patterns left to be discerned. Arda Reconstructed may have opened a door through which Tolkien scholars have only peeked. It may be years before we fully realize its value. I have struggled to write this preamble for the interview that follows because I wanted to convey the depth of my love for The Silmarillion. But also I wanted my questions for Doug Kane to reflect the depth of my own appreciation for a work like Arda Reconstructed without niggling over details. There is time enough to niggle about the various leaves.

MM: In the preface to Arda Reconstructed you indicated that the book arose out of an attempt to answer a question in an online discussion, gradually resulting in the book. You wrote: “It is my hope that this work will be of interest to a wide range of people, from the serious Tolkien scholar to a more casual reader.” As the book was only published in 2009 it’s “hardly been out there” very long, as scholarly works go. What has the reception been like thus far? Do you come across many citations?

DK: I’ve seen a few citations to the book, but not a large number so far. However, at the Mythopoeic Society conference this year, I was quite surprised to hear Verlyn Flieger say at almost the very beginning of the presentation of her paper on “the Stone, the Ring, and the Jewels” (a fascinating discussion of the role of the Arkenstone, the One Ring, and the Silmarils in their respective stories) something like “As Kane says … .” Actually, I was so startled that I didn’t quite catch what exactly she was citing me as saying, but she told me later that the paper is going to be published in the upcoming book dedicated to Tom Shippey, so I guess I’ll find out exactly what it was when that book comes out (assuming the citation survives the editing process).

Overall, I think the reception in the Tolkien community has been quite favorable, and most importantly it has stimulated interest in a subject that has largely been neglected up until the publication of Arda Reconstructed. Several of the individuals in the Tolkien scholarship community that I most respect have told me that they think that it is an important work, including Verlyn, John Garth, Doug Anderson, John Rateliff, Janet Croft and a number of others. It was reviewed quite positively by Nicholas Birns in Tolkien Studies (I particularly appreciated this statement: “Kane’s well-known online epithet, ‘Voronwë,’ is very suitable for his execution of this task, as watchful and respectful as Mardil the Good Steward’s rule no doubt was in the wake of the disappearance of King Eärnur. Kane’s textual scholarship is rigorous and is a model not only for Tolkien scholars but for scholars of more canonical authors, whose textual study is often pursued with less enthusiasm.”) The review in Mythlore by my good friend Jason Fisher was somewhat more mixed, but he certainly strongly acknowledged the importance of the study (calling it “a meticulously researched and valuable new reference work (one of all too few) on The Simarillion”), as did Charles Noad in a review that he wrote at the on-line site The LOTR Plaza (“an important and thought-provoking work and raises serious questions about the treatment of unpublished — and unfinished — literary material”). And the entry on The History of Middle-earth in The Literary Encyclopedia notes that Arda Reconstructed “is probably the most extensive analysis of The History of Middle-earth so far undertaken.”

Still, the book has also generated a fair amount of controversy as well. Christina Scull wrote a largely critical piece in Beyond Bree entitled “Reflections on The Silmarillion and Arda Reconstructed” in which she challenged a number of the points that I had made in the book. That piece, and some of the reaction to it, was then translated and printed in the Polish magazine Ancilima, along with an interview the editor had done with me. That interview, in turn, was reprinted in Beyond Bree, and Christina wrote another response to some of what I had said in the interview. It was certainly a lively exchange! But even Christina acknowledged subsequently in a blog post that the book is “a significant piece of research.” In addition, the noted Tolkien linguist Carl Hostetter engaged in a long discussion with me at my messageboard, thehalloffire.net, in which he also challenged some of my conclusions. He even quoted (with permission) from some correspondence that he had received from Christopher Tolkien himself, that included a report that Christopher had written in response to a sample of an early version of my manuscript (most of which report I myself had not previously seen before). Carl particularly objected to the assertion that the female characters had been reduced in the editorial process, and also noted that because not all of the constituent texts had been published in their entirety in The History of Middle-earth, it was not necessarily possible to determine what was editorial and what was authorial. While that has some degree of truth to it, it seems apparent that at the very least, the vast majority of significant variations from the texts printed in The History of Middle-earth and the published Silmarillion are editorial changes. It seems clear to me that most if not all significant manuscript alterations made by Tolkien himself are recorded (or at least referred) to in the History of Middle-earth (particularly since so many manuscript alterations, including often very minor ones, are recorded or at least referred). To deny that that is true would not only bring into question the value of Arda Reconstructed but of The History of Middle-earth itself. (Of course, what is “significant” and what is not “significant” could be a matter of opinion.)

However, the most gratifying response that I have received are the numerous comments that people have sent me either privately by email or at thehalloffire.net in which they indicated that they were inspired by the book to take a closer look at the extended material that is contained in the volumes of The History of Middle-earth, and that as a result of my book they had a greater appreciation of what a mammoth project the creation of the published Silmarillion was. Just the other day, someone posted at thehalloffire.net that they had just finished rereading Morgoth’s Ring and that “It was much more informative reading after reading Arda Reconstructed.” Comments like that warm my heart.

One cannot analyze a body of texts without drawing some conclusions. It would be extremely difficult to share such an analysis without including at least a few conclusions as well. In Arda Reconstructed Doug Kane argues that he has “identified five major types of changes to The Silmarillion that result from the edits made by Christopher Tolkien in the process of preparing the work for publication.”

It would require too much preamble to explain his points in detail (though Doug’s response to the following question provides some detail) but they are:

- The reduction of the roles or importance of female characters across the broader work.

- Eliminating many philosophical asides, explanations, or annotations (that were subsequently published elsewhere)

- Condensing important details or omitting them altogether from the published history.

- The complete reinvention of the Ruin of Doriath and the construction of the tale of the Nauglamir.

- “…removing the contexts in which these stories were placed” by omitting the super-narratives concerning Aelfwine and Pengolod.

–MM

MM: You identify five major changes that Christopher Tolkien introduced to his father’s (constantly evolving) concept of what The Silmarillion should have been. Have readers engaged you in your analysis of the depth and impact these changes? Do you feel that critical analysis of The Silmarillion should direct more attention to any or all of these topics than you’re currently seeing?

DK: Just as I expected would be the case, the most controversial of the major changes that I detailed in the book has been my identification of the reduction of the role of female characters in the story. Some people have strongly agreed with me on this point, and others have strongly disagreed (particularly Carl Hostetter, as I note above), but either way it has certainly generated some forceful feelings. None of the lively discussion that I have had on this point has convinced me that my analysis is incorrect, but if I had an opportunity to do any major revisions to the book, I would probably try to rephrase some of that to make it more clear that I don’t believe that there was an intentional action on Christopher Tolkien’s part to reduce the roles of the female characters in the story. However, I still believe that that is clear result of the editing process.

The other change that has generated the most discussion is the reduction of the philosophical discussion, again with some in strong agreement, and others in strong disagreement. Some felt that the audience wasn’t ready for such extensive philosophical musings in 1977, when the book was published. Others agree with me that it lessens the book’s impact.

A number of reviewers and other commentators have mentioned that they agree with me that the reduction in detail is in many cases unfortunate. I continue to believe that a less obtrusive editorial hand would have been preferable. Although the vast majority of the published book is based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s writing, barely a sentence is unchanged. As John Rateliff wrote in his lead essay in Tolkien Studies VI, “A Kind of Elvish Craft: Tolkien as Literary Craftman,” “Tolkien is a writer with whom details matter; they are the individual states, no two alike, from which he build his lighthouses on the Shores of Faerie. Changing a word here, a phrase there, a reference over yonder, can have a cascading effect.” In the case of the published Silmarillion so many minor changes combine to create a major affect on the whole.

As for whether critical analysis of The Silmarillion should address these questions more than it has thus far, that is a complicated question. Ideally, critical analysis of The Silmarillion should discuss the book as it exists, without necessarily attributing “blame” to the editor instead of the author. After all, the fact of the matter is that Tolkien never finished the book, and without his son’s efforts we never would have had it in any form. However, the other fact of the matter is that through Christopher Tolkien’s prodigious efforts we also have a glimpse at (most of) the raw materials from which the final product was constructed. For me at least (and for many others as well, I know), it is impossible to look at the published work in a vacuum. Thus when I say that critics like John Gardner compared The Silmarillion unfavorably to The Lord of the Rings because of its comparative lack of detail, I can’t help but consider whether different editorial choices would have mitigated such a complaint.

MM: There have been several failed online attempts to define a “Silmarillion canon” through the years. Do you think it’s feasible to argue for a canonical source text? Or do the narrative gaps — such as the incompletely retold story of Gondolin (of which the only full account dates to the Book of Lost Tales period) — make such a definition impossible, merely a whimsical fannish delight?

DK: The problem with the idea of a “Silmarillion canon” is that it is a moving target.

For some people, only what is included in the published work should be considered canon. But of course there are some things in the published work — like the Nauglamír being originally created for Finrod by the Dwarves — that Tolkien never wrote at all. And there are other things — like Gil-Galad being the son of Fingon — that were, as Christopher Tolkien himself concludes, no more than an “ephemeral idea” which were superseded in later writings that were not incorporated in the published work (in the case of Gil-Galad, the latest conception had him as the grand-nephew of Finrod, the son of Orodreth, who in that scheme had also been “moved back” a generation, becoming Finrod’s nephew rather than his brother).

Other people try to pin down the last-created version of a particular tale as “canon”. But that is not always possible to do given the information that we have, nor is it always clear that Tolkien always meant to supersede all earlier versions. A good example is the story of the Nírnaeth Arnoediad, the Battle of Unnumbered Tears. In the most commonly known version, contained in the published Silmarillion, Maedhros is delayed from meeting up with Fingon by the treachery of Uldor the Accursed. However, in a different (possibly later) version, Uldor is completely missing from the story and instead, Maedhros is intercepted by another force of Morgoth’s, and the eastern and western battles are completely separate. Which version is canon?

Still other people consider anything and everything that Tolkien wrote to be canon, no matter how contradictory, or how clear it is that that particular version had been superseded by a later version, a definition that to me renders the term completely meaningless.

Personally, I find it more meaningful to look at Tolkien’s legendarium as, if not precisely a true mythology, at least mimicking the form of a real world mythology. In a true mythology, you have a body of work created over a period of time by different authors, some of which overlap, and some of which contradict each other. Tolkien’s work is so vast that it successfully mimics this dynamic even though it is a body of work created over a period of time by a single author, rather than multiple authors. For me, the attempt to pin down “canon” is too limiting for such vast work. As Verlyn Flieger notes in her introduction to Interrupted Music (using the creation story of the Ainulindalë as a metaphor for Tolkien’s creation of his “mythology”), “The result has been that, over the course of time, the entire structure came to resemble real world mythologies in the cumulative process and temporal span of its composition, as well as in the scope of its subject matter.” She concludes that “The fact that Tolkien never completed his mythology is its flaw and its virtue, its greatest weakness that is also its greatest strength. The general outline (especially if we discount the never concluded time-travel stories) is secure, but the elements, as with most real-world mythologies are within their own parameters, dynamic and changeable.”

That dynamic and changeable nature is why I find the attempt to nail down a particular “canon” to be to limiting. But if it gives others pleasure to do so, I certainly have no objection to making the attempt. I would tend to agree that attempting to do so is more of a “fannish delight” than a scholarly analysis. But there is nothing wrong with that!

MM: As a practicing attorney you have (I would presume) had to piece together compelling arguments for or against various positions. Throughout Arda Reconstructed you mention some of your personal disappointments in Christopher Tolkien’s editorial choices, and you praise some of his choices. But Arda Reconstructed itself refrains from making a definitive statement on the quality of Christopher’s work. In the Introduction you cite Christopher’s reservation against entering into criticism of the “constructed” Silmarillion, then stating plainly for your readers that your book “enters into that question”. But did you intentionally refrain from making definitive qualitative judgements? Do you intend Arda Reconstructed to be only a second step in a path of gradually refined examination and critcism? Do you feel people would be justified in using your work to challenge or support Christopher’s editorial judgement? And do you feel that would be appropriate?

DK: There’s a really interesting dynamic at work here. As I say in the preface to Arda Reconstructed, The Silmarillion “has certainly had a greater influence on me than any other single work of literature that I have read before or since.” I maintain that this is true despite the book’s obvious flaws (I would agree with those who say that both The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit are “better” than The Silmarillion looked at purely as works of literature, which is perhaps not surprising given that those books actually were brought to their fruition by the author, and The Silmarillion was not). But it was impossible to determine at all to what extent those flaws were due to the author, and to what extent they might have been due to the editorial process, until Christopher engaged in the herculean task of presenting The History of Middle-earth, which provided an opportunity to compare the published text with at least the bulk of the constituent texts that were used in order to create that published text. So without that additional effort on the part of Christopher, it never would have been possible to make any judgment whatsoever about the editorial process, without having access to the original manuscripts (and I question whether anyone other than Christopher would have been able to successfully decipher those manuscripts; I am quite confident that I would not have been able to do so). It is true, as I note above, that not all variants of every text were included in the volumes of The History of Middle-earth. However, my research was able to conclusively show that the vast majority of the text of the published Silmarillion (other than the small percentage that is obviously editorial invention, primarily in Chapter 22 “Of the Ruin of Doriath”) can be directly traced to the constituent texts published in The History of Middle-earth, as shown in the tables that accompany the text. Therefore, I do think that people would be justified to use Arda Reconstructed to challenge or support Christopher’s editorial judgment, whether or not they agree with my own conclusions.

Christopher notes in the Foreword to The Peoples of Middle-earth that what became The History of Middle-earth “began indeed as an entirely ‘private’ study, without thought or purpose of publication: an exhaustive investigation and analysis of all the materials concerned with what came to be called the Elder Days, from the earliest beginnings, omitting no detail of name-form or textual variation.” In the correspondence that Carl Hostetter shared, Christopher further described this “History of The Silmarillion” as “more than 2600 very closely typed pages” and notes that the portions of The History of Middle-earth that relate to the Elder Days are a contraction of this longer work. My personal hope is that this “private” study will some day be made available on some level, even if doing so would render my book largely obsolete. I have no pretensions at all that Arda Reconstructed is the last word on the subject; rather, I hope that it helps open the door to a subject that has largely been ignored. As Jason Fisher says in his Mythlore review, in Arda Reconstructed I was “reaching in interesting new directions” and that in addition to shining “a brighter light on just how complex the underlying texts and their interrelationships really are, and how Herculean a task Christopher faced in bringing these inchoate works to a larger audience,” I provide “a blueprint to another possible “Silmarillion” … and a roadmap to further exploration in that mythopoeic space.” I hope that others will continue to explore that territory.

And after all that, I see that I have still avoided in typically lawyerly fashion to provide a direct answer to your request for a definitive statement about the quality of Christopher’s work. Well, I will say this. While it is true that with the benefit of hindsight I would likely have made a number of different decisions than Christopher did in creating the published work (as, in fact, he has acknowledged in various places in The History of Middle-earth that he would have done), and “my Silmarillion” (as Jason puts it) would likely be quite different than Christopher’s, I think under the circumstances that he faced, Christopher did an extraordinary job, and that The Silmarillion will stand the test of time as an important element of his father’s legacy.

MM: The Silmarillion was published in 1977. Have you read any books that you feel might compare to it? Is there a market in your own imagination for similar books, or is it for you a One-of-A-Kind that cannot be matched?

DK: I can honestly say that I have never read anything that compares to The Silmarillion (or more broadly, “the Silmarillion”). Of course, I am not as well-read as many others in the Tolkien community, but I have read some of the great older fantasy that precedes Tolkien (I particularly enjoy the works of David Lindsay, which I was exposed as a result of Doug Anderson’s recommendations). Very little of the newer “world-building” fantasy (such as that of George R.R. Martin) appeals to me. I think the reason is that “the Silmarillion” has a much greater depth than anything else that I have ever read; it is the “hidden vistas” that are hinted at in The Lord of the Rings (and in The Hobbit, to a certain extent, as well). Tolkien’s work is so remarkable in large part because it is so strongly rooted in both his deep abiding Christian faith, and his equally deep knowledge of and love for old pagan myths, as well as his unsurpassed understanding of language. Is there a market for similar books? Sure. But I question whether that particular unique combination of skills and passion will ever be seen again.

MM: For readers who want to see more about pros and cons of Christopher Tolkien’s editorial choices, can you recommend a few papers or books that explore the different points of view? Do you feel there is much Silmarillion construction criticism out there?

DK: To the best of my knowledge, my book is the first published work that actually analyzes Christopher Tolkien’s editorial choices. (Of course, now that I’ve said that, some of your readers are bound to prove me wrong. In fact, in his keynote address at MythCon this year, Michael Drout made a particular point of saying that every time someone says they are the first person to address a point of Tolkien scholarship, he is able to point to a previous example. So we’ll see what he or anyone else comes up with.)

The only papers that I know of that even peripherally address the subject are Charles Noad’s “On the Construction of The Silmarillion” in the MythSoc-award-winning book Tolkien’s Legendarium: Essays on The History of Middle-earth, and Jason Fisher’s “From Mythopoeia to Mythography: Tolkien, Lönnrot, and Jerome” in The Silmarillion: Thirty Years On. But Charles’s paper is really more about what The Silmarillion likely would have looked like had Tolkien completed it; he doesn’t really do any commentary on or analysis of Christopher’s editorial choices, except perhaps by implication (to the extent that the published version differs so much from what he indicates the book would have looked like had Tolkien finished it). Jason’s paper is a fascinating comparison of The Silmarillion with the efforts of Jerome in compiling the bible, and Lönnrot in compiling the Finish Kalvala, which actually does a very good job of bearing out the point that I made earlier about Tolkien’s work mimicking a true mythology. Jason goes as far as noting that Christopher’s decision to “undertake the challenge of brining the ‘Silmarillion’ papers into some kind of cohesive order” was not the only solution to the problem that he faced in presenting his father’s unfinished work, and that as a result of that decision Christopher was required to take an active hand in the narrative. But then he goes on to state that the extent of the changes made in the editorial process “is not immediately clear” but that “it might be possible to set passages from the published Silmarillion side by side with the corresponding drafts published in The History of Middle-earth (or with the original manuscripts in the Bodleian, where necessary) and to systematically ascertain the precise nature and degree of alteration made by Christopher Tolkien and Guy Kay.” What Jason didn’t know, of course, was that at the time that he was writing that paper, I was undertaking the exact analysis that he was describing.

(As a side note, I think it is interesting and fitting that Charles and Jason have written two of the prominent reviews of my book, given their own prior history with the subject.)

MM: In the book you provide 24 tables referencing primary and secondary sources for the paragraphs in each chapter of the book. Did you experiment much with the format and presentation of this information? For example, did you consider including (estimated) dates for when a source was (believed to be) composed (in the chapter-by-chapter tables)?

DK: Originally, the form that my manuscript took was very different than the final version. There were no tables, and the text described all of the changes in what I now realize was excruciating detail. Several people (including Christopher Tolkien, in response to the sample that I sent him) noted that such a close line by line comparison (“extending even to hyphens” as Christopher put it in the correspondence that Carl shared) would be unlikely to hold people’s interest. To give credit where it is due, it was David Bratman who after reading the original manuscript as an outside reader hired by the publisher considering publishing it, recommended that I move the paragraph by paragraph comparison into tables (removing most of the smallest details altogether) and concentrate in the text on describing the major changes, and to elaborate much more about what the changes meant, in my opinion. That proved to be excellent advice (although a heck of lot of work to accomplish) and I believe the final result was much more readable and interesting to a broader group of people (though the elaboration of my own opinion certainly also made it more controversial).

As for including estimated dates for when a source was believed to be composed, I do actually include that information. The very first table in the book is entitled “Source Material by Date” and lists each source included in the book, the date it is estimated to have been written, and the book that it was published in (mostly the volumes of The History of Middle-earth, but also Unfinished Tales, The Children of Húrin, and Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien).

MM: You did not discuss the maps very much. There have been a few attempts to redraw the cartography of Middle-earth (most notably Karen Fonstad’s Atlas of Middle-earth). Do you feel there is much room for discussion in the evolution of the maps? For example, would you have made some different choices than Fonstad did in blending pre-LoTR map information with post-LoTR maps?

DK: The maps were a bit of a tricky subject for me. I did play around with some discussion on the subject, but ultimately, I concluded that I wasn’t adding anything to what Christopher had already stated. I do think there is room for discussion about the evolution of the maps, but it would likely require that someone have access to the originals, and more importantly the cartographic skill of someone like the late Karen Fonstad. I love her book, by the way, and I wouldn’t even attempt to enter into any criticisms of what she did. Not because she is beyond criticism; I believe that no one is, including both J.R.R. and Christopher Tolkien (great as the work that both of them did was). Rather, it is because I don’t have the knowledge or skill to do so competently.

MM: As complex as The Silmarillion is in its published form, you feel one of the major editorial changes was the reduction of philosophical discussion. Do you feel that readers of The Lord of the Rings would understand the Elves better if that philosophical discussion could be restored in a new edition of The Silmarillion, or is it perhaps too complex for the narrative structure to support?

DK: As I mentioned above, this has been a subject that has generated quite a bit of discussion. In a review in Beyond Bree, Nancy Marsch particularly disagreed with my contention that the Athrabeth should have been included as an appendix, as per Tolkien’s specific instruction. She says that since this is Tolkien’s “most profound philosophical work” it required “a good understanding of the First Age in order to be appreciated. She further stated that since we only had The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil at that point that wasn’t background enough for people to understand something like the Athrabeth.

This is an interesting point, with perhaps some validity. On the other hand, had the Athrabeth been included as an appendix to The Silmarillion we would have had that background right there in that book! This is all the more true if it had been the more inclusive version that I have argued for, including such related material as the Second Prophecy of Mandos. I think that having had the opportunity to absorb the Athrabeth immediately after reading the First Age tales contained in The Silmarillion — and then the opportunity to continue to study both together over time (rather than having to wait an additional 16 years between them)– would have only enhanced people’s understanding. It seems to me that the fact that Tolkien wrote ‘Should be last item in an appendix’ on the wrapper of the Athrabeth indicates that he thought so too.

A number of others who have commented on the book have explicitly agreed with this point, whereas Nick Birns in his Tolkien Studies review took a middle road, acknowledging the value that including the Athrabeth and similar material would have had, but ultimately concluding that the “emphasis on what the hobbit-reader would have found as reassuring possibly explains the curtailment of the philosophical and religious aspects of The Silmarillion.” But even with that curtailment, The Silmarillion simply isn’t hobbit-centric and ultimately I think it was a mistake to try to make it more palatable to “the hobbit-reader” at the expense of minimizing its own qualities. Of course, now that The History of Middle-earth has been published in its entirety, readers do have the opportunity to obtain the deeper understanding of the Elves and Tolkien’s views on mortality, and the nature of spirit, and other highly philosophical topics. However, because of the dense, highly scholarly nature of The History of Middle-earth, the number of people exposed to it is likely to always be much less than those exposed to The Silmarillion itself, so many readers of The Lord of the Rings will never get that expanded understanding.

MM: You did not write much about Glaurung in the book. In fact, you mention Ungoliant more than twice as often as you mention Glaurung. How would explain that discrepancy? Did you feel the Glaurung passages were more stable than the Ungoliant passages? Would you say that Christopher was forced to make more choices about one character than the other?

DK: That’s a good observation, and the short answer is that yes, the Glaurung passages appear to be more stable than the Ungoliant passages, and therefore Christopher was forced to make more choices about her than him. There are two very different versions of the story of the darkening of Valinor, the version that appears in the published text in which Morgoth himself deals the fatal blows to the Two Trees, after which Ungoliant sucks up all of their light, and the later, more extensive version in which it is Ungoliant who deals the fatal blows, while Morgoth cravenly holds back. There is no comparable variation in Glaurung’s passages that I am aware of. However, this observation is complicated by the fact that Túrin’s story is the one part of the history of the Elder Days that Christopher did not completely present in The History of Middle-earth. He stated in the Foreword to The War of the Jewels that the history of his father’s work on “The Silmarillion” was largely completed with the publication of that book, and then clarified that it was incomplete only in the sense that he did not enter “further into the complexities of the tale of Túrin in those parts that [his] father left in confusion and uncertainty, as explained in Unfinished Tales.” So it is possible that there are more significant variations in Glaurung’s passages that are not addressed in either The History of Middle-earth or Unfinished Tales. However, there is also another factor at play here. Much of the discussion about Ungoliant in Arda Reconstructed involves additional reductions in the description of her interaction with Morgoth, both before and after the Darkening of Valinor. This is a product of the fairly severe contraction of that earlier part of The Silmarillion. In contrast, the tale of Túrin is told in much more significant detail (as is one of the other “Great Tales,” the tale of Beren and Lúthien, but not the other “Great Tale,” the tale of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin). That is another reason why there is more discussion about Ungoliant than about Glaurung in Arda Reconstructed.

Biographical Note

Douglas C. Kane is an attorney specializing in employment discrimination and harassment cases and other civil rights issues. He is also a Middle-earth enthusiast who has passionately loved the works of J. R. R. Tolkien for more than thirty years. He co-founded and runs the Tolkien Internet discussion site thehalloffire.net. His first book, Arda Reconstructed: The Creation of the Published Silmarillion, was published by Lehigh University Press in 2009, and was a Mythopoeic Society Scholarship Award in Inklings Studies finalist in both 2010 and 2011. A paperback edition has been released this year. Doug Kane lives in Santa Cruz, California with his partner, Beth Dyer, and two cats.

# # #

Have you read our other interviews with Tolkien scholars?