The Lord of the Rings is a soldier’s tale, a milieu story, a love story, a mythology, a eulogy for the pre-industrial era, a condemnation of industry, or all those things and more rolled up into one book. Tolkien implanted many of the moral questions he himself faced in the tale. Some biographers make much of Tolkien’s childhood; others assume there was greater impact from his war-time experience; yet others focus on his philological interests.

Of course, every major life experience left some sort of imprint – great or small – on the man who went on to write The Lord of the Rings. Imagine, for example, trying to write about war based on your memories of a terrible war that had stripped your country of hundreds of thousands of brave young men; only to learn that your own son must now go off to another terrible war. And at the same time many families found themselves on the frontline as bombs rained down upon their cities. How can a book written between wars and during a war, which deals with a war to end wars, not be inspired by those great wars?

That is the question J.R.R. Tolkien attempted to deflect in his Prologue but though he spared the casual reader a re-evaluation of the long dark hours of his own sojourns on battlefields, he could not refrain from leaving echoes of the marching columns of soldiers in his stories. Long lines of men and orcs stretch across several chapters, drawn from many nations, propelled into conflict by rulers who never consulted them on the choices they might have made for themselves. Therefore, it is fair to say that although other personal experiences might shed light on his writing, we can justify taking a snapshot of Tolkien’s life during the Great War and using that to learn more about the path he followed toward Middle-earth.

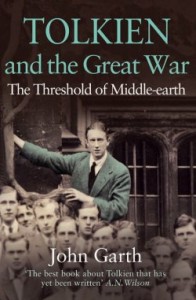

Few people have studied J.R.R. Tolkien’s personal war experiences in sufficient depth to provide us with much insight into how those experiences might have influenced his fiction. John Garth, author of Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth, is the most well-known Tolkien researcher to delve into the early years of the 20th century. If you have not read the book yet you should; it provides a great biographical portrait of a young man who sees his world divided between life and death. (An ancillary essay about the impact of the war on Tolkien’s circle of friends at Exeter College, Oxford, is available on John’s website, www.johngarth.co.uk.) And as Tolkien himself noted many years later, The Lord of the Rings is about “death and the search for deathlessness”. There is a context for that statement, one the full depth of which we shall never know, but I think John Garth has done a superb job of uncovering much of that context.

And so I asked him to answer a few questions for us, and to share his thoughts on some of these themes and others that are commonly associated with Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings. I began with one of the classic Tolkien motifs, and John provided a candid, gentle rebuttal to my own interpretation.

MM: J.R.R. Tolkien fans are intimately aware of his dislike for two aspects of modern civilization. First, he opposed what he called “The Machine”, which could be viewed as society imposing its will on individual members, stripping them of their creativity and identity — an experience that military organizations continually refine. Second, he regretted or hated the gradual destruction of the natural countryside and the encroachment of industrialization. Both of these themes appear in The Lord of the Rings. In your opinion, do you think the seeds of these strong feelings predate Tolkien’s war experience or did these feelings perhaps emerge in reaction to the horrors he experienced in France, especially in the Battle of the Somme?

JG: “The Machine” as a metaphor for society sounds more like Thomas Hardy than Tolkien. Tolkien saw actual machines as interposing between creator and craft to the detriment of both; and probably did feel that when the machine is multiplied everywhere (as in industrial society) then individuality is generally reduced. But primarily when he was talking about the general effect of “the Machine” he was thinking of the abuse of power by authority over society and nature, or over the Free Peoples and Middle-earth. This, from a letter to Milton Waldman (c. 1951), is how he defined “the Machine” with regard to his legendarium:

all use of external plans or devices (apparatus) instead of development of the inherent inner powers or talents — or even the use of these talents with the corrupted motive of dominating: bulldozing the real world, or coercing other wills [Letters no. 131]

So I’ll set aside the idea of “society” as an oppressive force – because I don’t think Tolkien saw it that way – and I’ll address the rest of your point.

Both the grinding down of the individual and the desecration of nature are everyday experiences in the modern world, although these days we can’t feel them as acutely as Tolkien, who was born in an era when road transport was horse-drawn. From almost as early as he could remember he had lived in and around Birmingham, one of the biggest industrial cities of the era, and as a lover both of nature and of rural life he was acutely aware of the encroachment of the town. He was also well aware of the Arts & Crafts Movement spearheaded by William Morris, one of his favourite authors (The House of the Wolfings, The Roots of the Mountains, etc.), and I’m sure his own views on the alienating effects of ‘mechanical’ labour were considerably shaped by those of Morris and his followers. Before the outbreak of war, Tolkien’s visual art and what little we know of his writings were concerned with the natural world or survivals of older things – ruins at Whitby in Yorkshire, “Wood-sunshine”, waves crashing on the Cornish coast. So his views on industrialization and on the destruction of the countryside were largely in place by 1914.

However, in the Great War, and especially in the trenches, the individual and the natural world were both attacked in new, horrifying ways, by both the military “Machine” and by military machines: entire woods and fields totally obliterated on the battlefield, and the individual reduced to a pawn or at worst a statistic on mountainous casualty lists. Even without the slaughter, all this would have been a shock to anyone, except perhaps workers already inured to life in factories and mines. To someone with Tolkien’s love of nature and craft, it must have been unbearable.

When he later underwent the further horror of watching his sons go off to war, he expressed his views about the specifics of military life at length in his letters to them. I have no doubt that much of The Lord of the Rings was propelled by the same original experiences: from the empathetic portrayal of the four hobbits separated by the fortunes of war, to the cathartic revenge fantasy of the Entish destruction of Isengard. You can taste his disgust at memories of the Western Front in the description of the scene before the Morannon.

Thomas Hardy lived from 1840 to 1928. He was an English novelist and poet perhaps most famous for writing Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Far From the Madding Crowd. Hardy’s work was noted for challenging Victorian England’s social and moral status quo. Hardy was not above giving Fate a role in his tales. The reader might note with curiosity that some of the titles Hardy’s books used included Under the Greenwood Tree, The Return of the Native, The Woodlanders, and Two on a Tower. All have a “Tolkienish” feel to them. –MM

JG: Links between specific experiences and particular events in The Lord of the Rings are impossible to prove, because Tolkien kept his cards close to his chest. He did acknowledge the influence of the Somme on the Dead Marshes and the Desolation of the Morannon (Letters no. 226, p. 303). He did say Sam Gamgee was inspired by the batmen (officers’ servants) and ordinary soldiers he knew in the Great War (Carpenter, Biography, George Allen & Unwin, 1977, p. 81). He did compare Faramir – a military leader forced to overcome his sensitivities and set down his books in order to do his military duty – to himself (Letters no. 181, p. 232). Given these examples, I think it’s therefore perfectly reasonable to look at passages in The Lord of the Rings and draw comparisons with Tolkien’s Great War experiences. C.S. Lewis did so in his review of The Return of the King, and he was not only a First World War veteran but also knew Tolkien as well as virtually anyone could:

This war has the very quality of the war my generation knew. It is all here: the endless, unintelligible movement, the sinister quiet of the front when ‘everything is now ready’, the flying civilians, the lively, vivid friendships, the background of something like despair and the merry foreground, and such heavensent windfalls as a cache of tobacco ‘salvaged’ from a ruin. (‘The Dethronement of Power’, 1955)

I’ve dealt with many possible influences in a couple of conference papers – “Frodo and the Great War” and “As under a green sea: visions of war in the Dead Marshes” (see bibliography below*). They fall into literal and metaphorical (or symbolist) categories; and the two are often inextricably intertwined, as they should be in good fantasy. You’re right, therefore, that Gandalf giving heart to the Minas Tirith defenders might recall some officer doing the same in the trenches; but common sense must remind you that he’s an idealized figure, indeed an angel, and that Tolkien may not have witnessed leadership quite so inspiring. But there’s a deeper way of connecting Gandalf’s role in the same scene with the First World War.

Briefly, one of the key themes of The Lord of the Rings is morale itself: the battle between despair and whatever reserves of “grit” the characters can find in themselves. Tolkien created his own myths of fear and courage in the mould of the First World War legend of “the Angels of Mons”, in which supernatural figures were said to have intervened to protect the retreating British troops in 1914. Gandalf falls somewhere between a flesh-and-blood leader and an angelic intercessor. His opponent, the Witch-King of Angmar, who unmans the defenders by his mere presence, is a kind of anti-Angel of Mons; demoralization personified.

To pursue the same theme, I’m struck by how Tolkien repeatedly embodies fear as a kind of miasma (the Black Breath, fog on the Barrow-downs, the Unlight of Shelob, the grey mist that flows out of the Paths of the Dead), and I suspect this was shaped by the smokes of the battlefield, and particularly by the ever-present fear of poison gas. I’m also struck by how Tolkien repeatedly shows fear reducing people to the level of beasts who crawl on the ground – think of Gimli at the entrance to paths of the Dead, or Merry dazed in the mud beneath the Witch-king’s steed – and I’m reminded of the phrase Tolkien used to sum up the experience of war: “animal horror”.

There’s so much more to say that I could write a book on it. But you also mention Frodo and Sam’s journey in Mordor, so I’ll deal with that briefly before we come to the next question. It’s obvious that trench warfare had little in common with the quasi-medieval Battle of the Pelennor Fields, in which (however woefully they suffer) heroes charge the enemy with flags flying. Trench warfare was almost static, and the real battle was psychological – morale again. I think Tolkien, in his examination of courage, was deeply interested both in the old-style courage of Beowulf or Beorhtnoth and in the modern courage of the soldiers he had seen in real battle. He explored one through characters like Éowyn or Aragorn; and the other through Frodo and Sam in Mordor. They are oppressed by the Eye, forced to creep and skulk as soldiers had been in the face of the machine-gun, aeroplane and surveillance balloon. Frodo is borne down by responsibility and by the metaphorical weight of the Ring: which is of course Tolkien’s arch-Machine – the symbol of the mechanization and abuse of power that he had seen run rampant on the Somme. The landscape is barren and blasted, as if the despoliation of the Western Front had overtaken an entire realm. Even in the tiniest details can be telling: the water has “an unpleasant taste, at once bitter and oily”. Why? There is no natural explanation. Tolkien has intruded an eloquent anachronism, surely remembering the Somme, where the water, carried in jerry-cans, was always petrol-tainted. Most importantly, in the Mordor sequence we see Frodo progressing towards what sounds remarkably like war trauma. His waking nightmares and increasingly distorted perceptions, his insomnia, his inability to recall comforting or strengthening sensations from the past: all these sound remarkably like descriptions of “shell shock”, as Tolkien’s generation first knew it

*Bibliography

Frodo and the Great War, in The Lord of the Rings, 1954–2004: Scholarship in Honor of Richard E. Blackwelder, ed. Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2006).

‘As under a green sea’: visions of war in the Dead Marshes, in The Ring Goes Ever On: Proceedings of the 2005 Tolkien Conference, ed. Sarah Wells (Tolkien Society, 2008), and (in slightly expanded form) in Myth and Magic: Art according to the Inklings, ed. Eduardo Segura and Thomas Honegger (Zürich: Walking Tree, 2007).

Welsh Gothic horror author Arthur Machen wrote a story, “The Bowmen”, which is attributed with inspiring the public to think that British soldiers had been granted divine protection during the war. The legend took on a life of its own without any apparent intent on Machen’s part. Rumors still persist about the angel, which was supposedly documented in a letter written 14 days before “The Bowmen” was published, by a British Intelligence officer (Brigadier-General John Charteris) that he sent home to his wife. Charteris, however, became embroiled in a wartime intelligence scandal about a fake German soldier’s diary that mentioned a fictitious “Kadaver factory”. Charteris’ credibility has been questioned for decades. –MM

MM: Your background is in English Language and Literature and yet you have intensively studied the history of the Great War as it related to Tolkien’s life experiences. Do you feel your work is more literary in nature or more historical?

JG: It’s about the conjunction of history and literature, so it is necessarily both. I studied history at school prior to university and it was probably my strongest subject, but at the time I was more drawn to literature so that’s what I pursued for my university degree. Tolkien and the Great War allowed me to explore both, which was wonderful.

MM: In your book, Tolkien and the Great War, you chose the title “Tears Unnumbered” for the section that deals with the Battle of the Somme. You provide details down to almost a minute-by-minute account of how the battle unfolded for Tolkien and his friends. How closely do you feel this battle served as the model for Tolkien’s Nirnaeth Arnoediad?

JG: Well, it’s not quite minute-by-minute: Tolkien was on the Western Front for four months, so that would have made for rather a long book! But yes, I tried to reconstruct what he and his battalion experienced in some detail when they were involved in actual attacks. The salient points where the Battle of Unnumbered Tears (in its various versions) echoes the Somme are as follows:

The high hopes beforehand. Soldiers in the run-up to July 1, 1916, had it drummed into them that the artillery had battered the German defences into dust and killed the German troops or sent them running; there were even cavalry squadrons marshalled to the rear to charge through the expected breach.

An assault on a wide front comprising various allies. In Tolkien’s sector there were the forces of Britain and the Commonwealth, including Australians, Canadians and South Africans as well as Indians; further down the line there were the French and their colonial forces.

The importance of timing and coordination between these forces. I’m not sure whether there was a similar problem between the different nations, but on a detailed scale, every account I’ve read of actions on the Somme reveals the dangers of mistiming and misunderstandings. This was the principal concern of Tolkien as battalion signals officer in charge of all communications for the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers – up to a thousand men. If a machine gun post had not been knocked out by the artillery, and no message had reached to the soldiers about to attack, they would advance into a hail of bullets. Communications were fraught, and the most reliable method was the runner, so delays were the rule rather than the exception.

There’s a specific example which I think left a deep impression on Tolkien. When he first arrived at the front and his battalion went into action, he stayed at HQ to help with communications (he hadn’t yet been promoted to signals officer but was one of the battalion signallers). One of the four companies in the battalion went on a night advance to take an enemy trench. The officer in command led them too far – right over the frontline German trench and into one of the enemy’s half-dug reserve trenches. They only realized their error when the sun rose. But at the same time the Germans saw it, and started firing at them. And meanwhile the British artillery was dutifully shelling that very spot, assuming it to be occupied by Germans, not by Lancashire Fusiliers. The only hope was to get a message back to the artillery or simply to head back into the “friendly fire”. In the end almost all the company was wiped out.

Further similarities with the Nirnaeth were the unexpected strength of the enemy; the irremediably awful toll of casualties; and the consequences for morale. But I think that’s enough detail for now.

The word fusilier refers to a soldier armed with a musket. The term was borrowed from French military usage in the 1600s. The Lancashire Fusiliers were an infantry regiment with a unit history extending back to 1688. The regiment saw action and won distinction in many of Britain’s most famous wars, including the Seven Years’ War, the Napoleonic Wars, and the Second Boer War. The regiment had units in every major campaign of the First World War. –MM

MM: Given that the war of the jewels was wholly comprised in an early form during and soon after the Great War, it seems obvious that the sense of futility the theme of the war conveys derives from the futility that Tolkien’s generation felt over the war. Do you think the entire theme is a response to the war, or is there perhaps something else, maybe something literary, a spark of passion that Tolkien preserved from an earlier time? Is futility a powerful or fully-developed theme in pre-War literature?

JG: Futility is absolutely epitomized by the First World War; there is no more eloquent symbol of it. During the Somme alone, more than 300,000 men were killed, counting both sides; yet the battle lines barely moved, and the ground they fought for was obliterated in the process. And then in 1917 the Germans beat a tactical retreat, allowing the Allies to simply walk over the ground their friends had died on. It must all have seemed so meaningless. And yes, I believe that overall sense of futility gave some of the shape and meaning to “The Book of Lost Tales”. It must be emphasized though that Tolkien’s distinctive virtue as a writer was then, and remained later, that he refused to surrender to the sense of futility. That’s why in The Lord of the Rings we have Théoden’s “remoralization”, as you might term it, to demonstrate the folly of Denethor’s demoralization. And in the darkest of the Lost Tales, even Turambar – though driven in the end to suicide by Melko’s machinations – has thoroughly redeemed himself by his tenacity and courage. Was there an earlier example that Tolkien drew upon – an example of courage in the face of apparent futility? Yes, at least one: the idea of “Northern courage”, the moral fibre that allows the heroes of Norse myth and Anglo-Saxon verse to fight on against ultimately unbeatable odds. In “The Battle of Maldon” this is encapsulated in the famous lines of one of Beorhtnoth’s retainers:

Hige sceal þe heardra, heorte þe cenre,

mod sceal þe mare þe ure maegen lytlað.

– as translated by Tolkien: “Will shall be the sterner, heart the bolder, spirit the greater as our strength lessens.” (The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son)

MM: Looking at the details you provide in your book, one wonders how you assembled all the sources. What was the greatest obstacle for you and how did you overcome it? Was there a moment where you felt like, “Wow! I’ve found a gold mine of information?”

JG: I love research. When other people might kick back and watch the game, I’d rather be in some archive following a trail of clues to unlock a mystery. It can be a slog but it is addictive and the moments of discovery are real tonics for the soul. The biggest obstacle may have been when I first signed a contract with HarperCollins, and realized that I would now have to start turning three years of research into something other people would actually read. The solution was obvious, though it took me a few months to act on it: simply to start. But all the way through the next two years – and especially until I reached the halfway mark – there were times when I felt as if I were scaling Everest. The solution to that was to visualize my task not as a whole but in discrete chunks – make lots of molehills out of the mountain. And of course when I felt it was all too difficult, I could always contemplate what the men I was writing about had had to endure. That quickly brought my problems down to size.

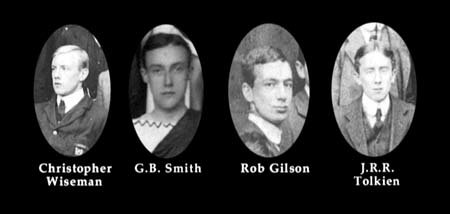

My first “Wow!” moment was at the very beginning, when I had just decided it would be intriguing to study what Tolkien did in the war, and what it meant when he wrote on a poem that it had been written at “Brocton Camp” in 1916 or whatever. I forget exactly how I had made a start, but within two or three weeks I happened to hear on the news that the service records of First World War officers, which had been closed for 80 years, were just about to be made public for the first time. So I was literally the first through the door of the National Archive (then known as the Public Record Office), and the first to look at Tolkien’s service record, which includes the record of his enlistment and maps out what he did after being invalided back to England from the Somme. Another “Wow!” moment was tracking down the family of RQ Gilson, and being invited to make full use of Gilson’s papers: a tin box full of letters he had written from the training camps and the trenches, full of references to his and Tolkien’s circle of friends – not to mention fascinating and powerful in their own right as records of a typical officer’s experience up to the first day of the Somme. The other big moment for me was going to the Bodleian Library in Oxford and finally seeing the letters between the TCBS. But every page is probably the product of several mini-discoveries too: military papers located, collated and compared; breakthroughs in understanding complex topics; connections made between disparate threads.

TCBS stands for “Tea Club, Barrovian Society” and was the name of an informal group of friends who met at King Edward’s School, Birmingham; they regularly gathered at the city’s Barrow’s Stores. The main members of the group were J.R.R. Tolkien, Geoffrey Bache Smith, Christopher Wiseman, and Robert Gilson. Of these four very close friends, only Tolkien and Wiseman survived the war (see more detail in John’s answers to the next two questions). –MM

MM: What misconceptions about Tolkien’s war experiences do you feel your book best addresses? Are there still misconceptions or beliefs where you think to yourself, “I wish I had addressed that better” or “If only I could have delved deeper into that?”

JG: The only account of Tolkien’s war years had been Humphrey Carpenter’s few pages in the authorized biography published in 1977. Carpenter’s is a fascinating, highly readable book, but it skims lightly over everything, the Great War included. There’s no sense of the magnitude of events, of what he and his battalion were doing in the actions Carpenter mentions, or of what they were doing between them. Carpenter makes small errors and unfortunate elisions – understandable, in most cases, because no one had made a full study of what Tolkien did, and Carpenter was not concerned with military history. But he also fails to note some really powerful points of fact.

After telling of Smith’s death, he quotes from the deeply moving letter in which Smith called himself “a wild and whole-hearted admirer” of Tolkien’s work. Carpenter says this was written “not long before” his death, which would lead one to assume perhaps a few weeks had elapsed. In fact it was written a full nine months previously, and three months before the Battle of the Somme even started. Carpenter misses out the whole purpose of the letter, which was to urge Tolkien to publish his poetry before coming out to “this orgy of death and cruelty”. And because his research was confined to Tolkien’s papers, he didn’t appreciate the acute fear behind Smith’s phrase “If I am scuppered tonight – I am off on duty in a few minutes”. Smith was about to lead a night patrol in No Man’s Land – the most dangerous part of an officer’s duties. The officer who led the previous night’s patrol had been taken prisoner, fatally wounded. Smith thought this might well be writing his final letter to Tolkien.

When I started researching what Tolkien had done, I felt a strong sense that there was a connection, or multiple connections, between what he wrote and what he was experiencing at the time – whether as a student torn between duty and fear of enlistment, or as a soldier about to embark for active service, or as a survivor of the Somme. The connections might be a matter of timing, or mood, or even theme; but Carpenter was clearly not interested in making such connections.

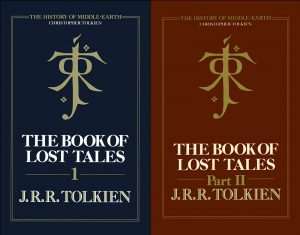

For “The Fall of Gondolin”, written in hospital directly after the Somme, Carpenter states only that “it is not unreasonable to suppose that the great battle which formed the central part of the story may owe a little of its inspiration to Tolkien’s experiences on the Somme…. but in any case these were only superficial ‘influences’…” There’s no indication of the central role played in the attack on Gondolin by metallic, mechanical, troop-carrying “dragons” (remember, this was published before The Book of Lost Tales), or of the remarkable similarity these have to the tank, the British secret weapon which had been rolled out in Tolkien’s own sector of the battlefield a couple of months earlier.

I have tried to rectify this by constantly ensuring I place Tolkien’s writing in context of external events. But I’ve also tried to avoid the opposite error, which would be to claim that everything he wrote was a direct response to the war in the most obvious ways. The real situation as I see it is much more subtle, multi-layered and interesting than that.

I’d still like to address one of the widespread urban myths about Tolkien’s war experience, which is that he got lost behind enemy lines on horseback and chased by enemy Uhlans (an event which is claimed as inspiration for scenes in The Lord of the Rings). It’s patent nonsense, but it only emerged after Tolkien and the Great War appeared. But I ought to have made clearer — when I wrote about Tolkien’s student experiences in the King Edward’s Horse cavalry regiment — that the statements about his knack with horses came from a slightly dubious source. I’ve made a note of most known errors in an errata page on my website, but this one will require a bit more discussion.

I wish I had been able to read “the very large body of letters he wrote between 1913 and 1918 to Edith Bratt”, mentioned by Carpenter in the introduction to The Letters of JRR Tolkien. Though “highly personal in character”, I am sure they would have shed further light on Tolkien’s activities in the war and his feelings about it. But the Tolkien Estate was very generous in allowing me to examine his military papers and associated correspondence, which give precise details of his movements on the Somme and show vividly how he and his friends in the TCBS fared under the shadow of war.

Cavalry charges play an important role in Tolkien’s Middle-earth fiction, from the horse-riding Noldorin archers of Hithlum pursuing Glaurung back to Angband to the ride of the Rohirrim over the Pelennor Fields. The First World War is generally credited as the last war in which large cavalry forces were deployed, although there were incidents in the Second World War where horses were used in combat. The last cavalry charge conducted in a major war occurred in 2001, when approximately 30 American Special Forces members and Afghan fighters charged a Taliban force (which included at least one tank). The United States erected a memorial to the Special Forces soldiers who fought in Afghanistan across from the former World Trade Center on November 11, 2011 (Veterans Day in the US, Remembrance Day in the United Kingdom, and still known as Armistice Day in France and Belgium). –MM

MM: There is a note in Tolkien’s late essay “The Shibboleth of Fëanor” (published in The Peoples of Middle-earth), where he states that the loremasters of the Eldar seldom actually wrote down their knowledge — but that they were most likely to do so in time of war, especially if they sensed they may be facing death themselves. Do you have a sense for how much “lost knowledge” Tolkien felt the war took away from his generation, knowledge that was never set down in print? Is this perhaps only an extrapolation on his part, a sort of “what if” scenario playing out in his mind as he works the logic of his stories, or was there a real precedent in the British World War I experience?

JG: The loss of talent in the First World War is incalculably vast. Survivors felt that the cream of a generation – the “Lost Generation” – had been destroyed. Like Tolkien, officers were drawn from among the highly educated, with all the benefits of the best schools and universities behind them. Many would have gone on to be scientists, artists, poets, historians – specialists in every conceivable field of knowledge. But what actually happened is that they were put in the forefront of battle, sent to lead other men into raking machinegun fire. Their casualty rates were therefore even higher than those among the men they led.

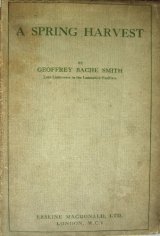

One example can speak for many: TCBS member Geoffrey Bache Smith, who died on the Somme in December 1916. His death was particularly futile, because the battle itself had been over for some weeks, and he was just overseeing roadworks when he was struck by fragments from a stray shell, which led to gangrene. But he left quite a body of poetry, some of it showing considerable promise; the signs were that if he had lived on, his output would have continued and his powers grown. In his poem “The Burial of Sophocles”, Smith expresses grief at talent wasted by war when it should have reached full maturity:

O seven times happy he is that dies

After the splendid harvest-tide,

When strong barns shield from winter skies

The grain that’s rightly stored inside…

When Tolkien and fellow TCBSite Christopher Wiseman edited Smith’s poems and had them published in 1918, the title they chose was A Spring Harvest. That says it all. Smith’s poetry never reached its full “harvest-tide”, and had had to be gathered out of season, in the springtime of his years when it was not full-grown.

So yes, there was a very poignant precedent for what Tolkien envisaged in that note from “The Shibboleth of Fëanor”, or rather (because we are not just talking about GB Smith) there were many. And Tolkien had been conscious of the loss even in 1916 before he went out to fight in France himself. He tried to get his own early “Middle-earth” poetry published, having been explicitly urged to do so by Smith and the others before he faced the dangers of the Western Front himself. In a poem, “The Wanderer’s Allegiance”, he described Oxford as a citadel of learning which might act as a bastion against the destruction of so much life and talent. There’s a strong echo of this in the “Shibboleth” note were he writes: “books were made only in strong places at a time when death in battle was likely to befall any of the Eldar, but it was not yet believed that Morgoth could ever capture or destroy their fortresses”.

A shibboleth is a practice or belief that distinguishes one group of people from others; the word is taken from a Biblical story about how the pronunciation of the word shibbólet was used to identify Ephraimites from Gileadites. “The Shibboleth of Fëanor”(so-named by Christopher Tolkien) explains how the Noldor became linguistically divided into two groups early in their history, laying the foundation for their future divisions into multiple kingdoms. –MM

MM: In your article “Tolkien, Exeter College and the Great War” you chronicle Tolkien’s youthful exuberances away from his guardian’s care and oversight. He seems to have done everything but study. Would you say that is rather Tookish? Do you think the Tooks owe something to life at Exeter?

JG: When Tolkien was first devising his Elvish language Qenya (or Quenya), he was happy to make explicit connections between the world he was inventing and his own life. So his fiancée Edith Bratt and his brother Hilary both feature, lightly disguised as minor Valar; so does Tolkien. But the invention of the Tooks was a long way off: the late 1920s or early 1930s I presume, when he was writing The Hobbit. I think Tolkien’s exuberances at Exeter College were probably quite typical for a student at Oxford with a little money and lots of unaccustomed freedom. As a don at Oxford, and before that as a lecturer in Leeds, he naturally continued to see young whippersnappers carrying on the tradition. And by the time the Tooks came along he was a father of four children, who I’m sure were prone to the odd bout of exuberance. I’d hesitate to look for such a specific source for Tookishness – which in any case is something more than mere exuberance: capricious adventurousness too. It’s also worth mentioning here that the idea that Tolkien’s hobbits (and their surnames) were inspired by stories of Kentucky folk told by his American Exeter College friend Allen Barnett (promulgated in Daniel Grotta’s old unauthorized Tolkien biography) appears to have very little substance.

Note: Due to scheduling issues and my own health this interview was conducted a few months before I wrote my short question-and-answer piece, “What is the Origin of the Took Family Name?” I in fact wrote that article in response to a fan question, and not as a consequence of asking John this question. The little bit of research I was able to do at best offers only an alternative possible explanation for the family name but resolves nothing. The Tooks remain a curious mystery in Tolkienana. –MM

MM: One of the “odd man out” incidents in Tolkien’s stories is the death of Arvedui, who fled north after Arthedain was overrun by the forces of Angmar. Arvedui and his companions sought refuge in an abandoned Dwarf mine and then turned to the Lossoth (the “snow folk”) for help. The Lossoth took Arvedui and his men out onto the ice where they were picked up by a rescue ship sent by Cirdan. The ship went down and Arvedui, his men, and the mariners all perished. Can you think of any incidents within Tolkien’s early lifetime that might have influenced this account (such as the doomed expedition of Captain Robert Falcon Scott or the death of Lord Kitchener, who died aboard the HMS Hampshire when it struck a mine off the Orkney Islands in 1916)?

JG: Here we move into one of the areas I would have liked to have covered in Tolkien and the Great War but excluded because otherwise I would never have completed the book. Ernest Shackleton’s great account of his 1914 Endurance voyage to Antarctica was one of my period readings during the writing process. I’d be very surprised if Tolkien didn’t know it, and he would certainly have been fully aware of what happened on the expedition: the loss of the ship, the incredible journey over ice hauling lifeboats, the wintering of most of the crew on Elephant Island under upturned hulls, Shackleton’s trip across tempestuous South Seas in a tiny boat to the island of South Georgia to summon help. It’s one of the epic adventures of Tolkien’s time, and indeed of all time. (A curious detail is that one of the ship’s boats, the Dudley Docker, was named after a sponsor, Birmingham industrialist Frank Dudley Docker, 1862–1944 – a former pupil of King Edward’s School in Birmingham, like Tolkien.) We know that Tolkien was interested in polar exploration, at least enough to know Fridtjof Nansen’s Farthest North (which he cites in Letters), and it comes through in the legendarium not only with Arvedui and the Lossoth, but also the crossing of the Helcaraxë. He grew up in an era when the world still contained unknown lands – only some of the edges of Antarctica had been mapped – and the explorations were followed avidly by many. Shackleton, Scott, and the earlier tragedy of Sir John Franklin’s expedition to seek a sea route around north of Canada – another possible influence on the tale of Arvedui – were imprinted in the popular imagination.

Investigating the background to Tolkien’s imagination in this way can really add further riches to reading his legendarium. It’s good to know where he’s coming from.

Biographical Note

John Garth is the author of Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth, winner of the Mythopoeic Award for Scholarship; published in Britain by HarperCollins and in the US by Houghton Mifflin, and since translated into Italian and Chinese. He also voiced the HarperCollins audiobook. John has spoken on Tolkien’s war at conferences in America and Europe, at Britain’s National Army Museum, and on television, radio, and DVD (including Peter Jackson’s Return of the King). His reviews of books including The Children of Húrin and The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún have appeared in the Times Literary Supplement and major British national newspapers. He is a contributor to the Routledge J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia and to the upcoming Wiley-Blackwell Companion to J.R.R. Tolkien. A freelance writer, editor and researcher, he lives with wife Jessica and daughter Lorelei. His website, with more information and more of his writing, is www.johngarth.co.uk.

# # #

Have you read our other interviews with Tolkien scholars?

[…] Today we have published a new interview with a Tolkien scholar by Michael Martinez. Please read An Interview with John Garth. John is the author of Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth and he is widely […]

[…] On the Interviews with the Scholars Series Posted on June 15, 2012 by Michael Martinez tweetmeme_style = 'compact';tweetmeme_url='http://blog.tolkien-studies.com/2012/06/15/on-the-interviews-with-the-scholars-series/';http://blog.tolkien-studies.com/2012/06/15/on-the-interviews-with-the-scholars-series/On the Interviews with the Scholars SeriesTolkien Studies BlogThis week I have published the latest and (for now) last in my series of interviews with Tolkien scholars at the Xenite.Org Middle-earth Website. I invite you to read An Interview with John Garth. […]

Thank you for posting this wonderful and informative interview. Mr. Garth’s book is fascinating and insightful. This interview makes me want to read his book again. Tolkien’s war experience, including the loss of his friends, cannot but have had a profound impact upon him, and his refusal to be demoralized and bitter as were many of his generation, is nothing short of heroic.

Wow… just wow. Wonderful interview. It give so many rare informations.