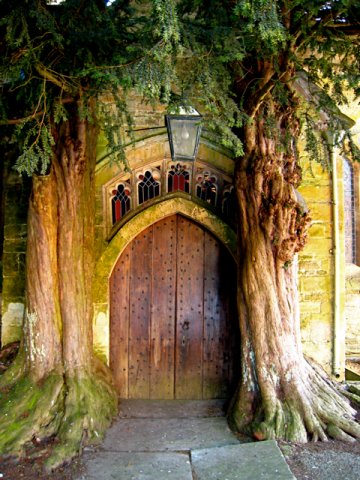

Q: Was Tolkien Inspired by the Door of St. Edward’s Church in Gloucestershire?

ANSWER: Do you mean the famous medieval church whose (north / west) door is framed by two yew trees, the one J.R.R. Tolkien failed to mention in any text of which I am aware? Are you talking about the small church in Gloucestershire, St Edward’s Church, Stow-on-the-Wold, that no credible Tolkien scholar has mentioned? I don’t know. What do you think?

The door is quite interesting, as doors go, because of the two trees standing beside it. Other than that it’s hard to see much of a resemblance between what J.R.R. Tolkien drew for The Lord of the Rings and what the church door looks like. I rather suspect people are comparing the west church door to Peter Jackson’s impressive visual rendering of the west-gate of Moria in “The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring”, although his doors (like Tolkien’s) were made of stone.

So, before I proceed further and infuriate half the population of Gloucestershire (which is just to the west, northwest of Oxfordshire), let repeat me myself: I don’t know. There is, to my knowledge, no record of any connection between J.R.R. Tolkien and that specific church despite its close proximity to Oxford. It seems like half the towns and villages throughout England, Wales, and Scotland are trying to lay claim to Tolkien’s legacy and, honestly, it’s impossible to debunk everything that comes out in the British press or an occasional architectural blog or book.

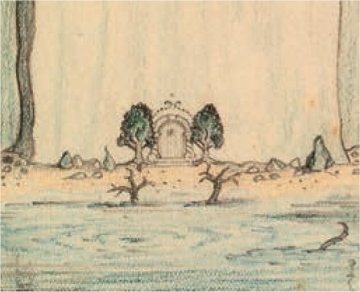

Debunkery is supposed to prove the falsity of, well, false claims. That’s not so easy to do when you don’t have a list of specific sources for Tolkien’s life events. We do, however, have a record of his illustrations for the west gate of Moria. The early draft, described by Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull in J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator, was rather plain and simple. However, at some point Tolkien drew a colored pencil sketch that Hammond and Scull reproduced as plates number 148 and 149 (pg. 157). They also reproduced four preliminary sketches for the west gate illustration that eventually appeared in print. I cannot check The Art of the Lord of the Rings to see what Hammond and Scull wrote in that book. I was only able to find Artist & Illustrator and The Art of the Hobbit on short notice. Sorry.

When you compare the illustration that was published in LoTR to the picture of the door at St. Edwards, Stow-on-the-Wold it’s obvious this is not what has people so excited. Clearly the illustration only bears a slight resemblance to the church door. And Hammond & Scull note in Artist & Illustrator that the west gate illustration appears to follow a pattern from two much earlier works by Tolkien. The works are titled “Before” (plate 30) and “Wickedness” (plate 32). Both drawings represent doorways framed by two standing things.

This duality motif appears in some of Tolkien’s other illustrations. He became adept at drawing scenes dominated by symmetry. We are naturally attracted to symmetrical shapes and scenes. Symmetrical images appear to be balanced or unbiased to the observer. There is an odd beauty to them and they stand out from the discordant, random imagery we are inundated with every day.

The “Yew Tree Door”, as it’s also known, apparently has many counterparts throughout the English countryside. While other doors framed by yew trees may not be quite as distinctive as the door at St. Edward’s Chuch, Stow-on-the-Wold, the custom of planting trees by doors is quite ancient according to some sources. And because yew trees can live for several centuries it’s entirely possible that J.R.R. Tolkien saw the “Yew Tree Door” and was inspired by it. But he could have been inspired by something else altogether.

People have been reporting that the church door was the inspiration for Tolkien’s illustration for years. The idea has become firmly fixed in the locals’ imagination and is spreading across the Internet. Without confirmation from the author or his family, however, it’s simply impossible for us to know what the truth is. But God forbid that Wikipedia should start reporting this rumor. We’ll never get to the bottom of the mystery. (Perhaps I should mention here that Wikipedia says the yew trees stand beside the north door, not the west door.)

The town of Stow-in-the-Wold is located in that part of England (and Gloucestershire) known as “the Cotswolds”. The name drips with Tolkienian etymology. The Wold, for example, is a place in Rohan: a green grassy area composed of rolling hills. The Cotswolds is composed of gently rolling hills with Shire-like copses of trees. The word wold is believed to be derived from Germanic wald, meaning “forest”. So the Cotswolds were once forested and they lost their trees — much as Minhiriath lost its tree cover in the Second Age.

The cot(s) part of the name may derive from cote, meaning a small building. From about the 1400s the word cot was used of small buildings for animals, as in sheepcot. The Cotswolds was once a vast sheep-herding region (I don’t know about today), or so this interpretation of the name implies. Ironically, that is just the popular etymological history of the name. The English Place-Name Society apparently holds that Cotswolds really descends from “Cod’s Wolds” (Cod being a personal name of some chieftain or wealthy man living long, long ago). The entire etymological argument branches out from there (pardon the pun) in what I am sure would have tickled J.R.R. Tolkien’s fancy from stem to leaf.

Another local tradition is that Bell Inn Pub, located in Moreton-in-Marsh, is supposed to be the inspiration for the Prancing Pony Inn. This claim has apparently been recognized by the Tolkien Society, so I’m not going to call it into question. Although …

# # #

Have you read our other Tolkien and Middle-earth Questions and Answers articles?

Hi, Mr Martinez:

My name is Tianluo_Qi, the editor of one Chinese web newsletter about Tolkien, Arda NEWS. The other day, I ran into your Tolkien blog by accident and thought the Q&A which you’ve been working on for a long time is really excellent and inspiring. So, things are that we want to translate some of your posts. Don\’t know if we have that honour? Of course, we will stress that you are the original writer in our post, but as a non-profit fan-run newsletter, we are not able to pay you any royalty. Well, looking forward to your response, and you can contact me via the following Gmail:

TLQ