Q: What Did the City of Dale Look Like?

ANSWER: In case it’s not obvious, I tend to allow the more difficult questions to sit in my email for a long time. This question was submitted by a reader in April 2017. The full question reads: “I’ve read a good number of your articles on Dale, and really enjoy some of the inferences you make. Specifically i’m wondering what you think Dale would look like as far as design and architecture. I always imagined it as a quaint Germanic type town, similar to Rothenburg.” So, technically, he is asking what I, Michael Martinez, think Dale would have looked like. I rewrote the question for this article because I would like to know what others think it would have looked like. Please feel free to share your thoughts in the comments below. Of course, only J.R.R. Tolkien knows what he felt it should have looked like.

As you can see from the picture of Rothenburg I have included in this article, this old medieval town has at least one very beautiful street. Based on other pictures I have seen of the city, I am sure I would enjoy walking through its streets very much. One picture does not do the city justice. The town wall is magnificent. And, of course, many people have seen what Peter Jackson’s film artists imagined Dale should or would look like.

As I have said many times through the years, Middle-earth is not medieval Europe. You can find a lot of medieval influences in Middle-earth. And modern influences, and classical influences. Middle-earth is a melting pot of historical memes, themes, and mythologies. You could probably make a very strong argument for styling Dale on, say, an ancient Lusatian town. Okay, maybe not the Lusatian culture. Biskupin, the most well-known Lusatian town, was only discovered in the 1930s and I’m not sure Tolkien would have learned much about it by the time he was writing The Lord of the Rings. He almost certainly had heard nothing of the town by the time The Hobbit was published in 1937.

It seems important to me to find a historical context for J.R.R. Tolkien’s knowledge of the ancient world at the time he wrote about things that people compare to the ancient world. For example, he is not likely to have been heavily influenced by the Sutton Hoo excavation because that happened in 1939, well after The Hobbit was written and too close in time for The Lord of the Rings to have been greatly influenced by subsequent scholarship. The first major scholarly works were published in 1940, during the height of the war. The initial report was very rushed and omitted many details. It’s very doubtful that article could have strongly influenced J.R.R. Tolkien’s vision of Middle-earth in any way, especially as the report focused on what had been learned about the ship.

Dale, of course, is not located in a part of Middle-earth that owes much to Anglo-Saxon England anyway. Dale and Erebor are, through their nomenclature and personal names, influenced by Scandinavian literature and mythology. Nearly all the Dwarves’ names are taken from the Icelandic “Völuspá”, which is dated to at least the 13th century (1200s CE). Current scholarship seems to favor the idea that the poem’s roots extend back to the 10th century (900s). We don’t know for sure. And, honestly, the Scandinavians and their East German cousins were already literate and writing in runic alphabets as far back as 2000 years ago. We don’t know if they had literature that is now lost, but everyone agrees that what we have for “Völuspá” is a medieval Scandinavian poetic tradition.

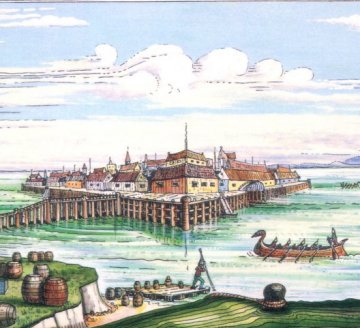

But Iceland and Scandinavian mythology are not the only influences Tolkien drew upon for the setting of that part of The Hobbit which lay to the east of Mirkwood. There is also Lake-town, which some scholars argue was strongly influenced by prehistoric Swiss lake villages. However, as my article notes, Tolkien’s illustration of Lake-town reveals more sophisticated architecture than one finds in the reconstruction of late Neolithic villages; he clearly blended medieval elements into the lake village concept.

Given that Lake-town and Dale’s histories and languages are so closely tied together, it is impossible to say that either should have been solely influenced by Scandinavian or Germanic culture. I do believe, though I cannot prove this, that Tolkien implied that Dale+Erebor would have stronger Scandinavian influence and Lake-town would have stronger central or west Germanic influence. If you are comfortable saying that Rohan and perhaps the Beornings were heavily influenced by Anglo-Saxon (pre-Conquest) England, then it seems to feel right to say that Lake-town was strongly influenced by Swiss and central European Germanic culture. By extension, we can arbitrarily (without any direct support from Tolkien himself) argue that Dale + Erebor may have been most strongly influenced by Norwegian and Icelandic culture.

Iceland was apparently discovered by Irish monks, who began wandering the seas sometime in the 400s or 500s. They made their ways to America, Iceland, the Faeroes, and continental Europe before their star faded. The first Norse settlers in Iceland may only have been seasonal visitors, but the first permanent settlers in the mid-800s found Gaelic monks living on the island. They may have made a permanent home in Kverkarhellir cave but I am not sure J.R.R. Tolkien would have known that.

If we assume that Dale was built like Viking Age towns in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Iceland then that means there was probably a wooden wall or dike surrounding the town. The buildings could have been a mix of timber frame homes and stone-and-turf homes. Farms were more likely to be built with stone walls and foundations and turf rooves. The towns were more likely to be built wholly in wood. Thorin mentions farms in or near the valley of Dale. Elrond remembers how Smaug burned the banks of the River Running. And Thorin mentions the bells of the town two or three times.

When Balin, Fili, Kili, and Bilbo climbed Ravenhill on the south side of Erebor, they looked out upon the ruins of Dale: “and gazing out from it over the narrow water, foaming and splashing among many boulders, they could see in the wide valley shadowed by the Mountain’s arms the grey ruins of ancient houses, towers, and walls.” Balin tells his companions: “The mountain’s sides were green with woods and all the sheltered valley rich and pleasant in the days when the bells rang in that town.”

Later on in the story Balin added the following detail: “The road from the Gate along the left edge of the stream seems all broken up. But look down there! The river loops suddenly east across Dale in front of the ruined town. At that point there was once a bridge, leading to steep stairs that climbed up the right bank, and so to a road running towards Ravenhill. There is (or was) a path that left the road and climbed up to the post. A hard climb, too, even if the old steps are still there.”

With only a few mentions of Dale’s ruins it’s hard to imagine much but the fact that the ruins were grey implies to me that they were made of stone. The bells would have been in towers. The towers could have been built of stone. The majority of the town could have been built of wood, though. The walls could have been a combination of dike (earth piled up) and stone. I imagine the farms would have used a classic longhouse style for their buildings. We already know that Beorn lived in a longhouse and there is some evidence of longhouse architecture in Rohan (Meduseld was a great hall built in the style of a longhouse).

The wattle and daub architecture of Rothenburg probably strikes many people as appropriate for the towns of Middle-earth, but there is just one problem with that assumption: Tolkien does not mention wattle and daub. He mentions a lot of stone-work, and there are bricks in the Shire, and wooden homes in Rohan. But there is not one occurrence of wattle and daub. “Wattle” refers to the wood-framing but “daub” refers to the material used to fill in the walls. Daub was made from clay, mud, soil, sand, animal dung, and/or straw. So you’re probably not looking at “wattle and brick” or “wattle and stone” in any of those picturesque houses you see in typical “medieval” villages. Actually, that style is often described as “Tudor” so it would be a Renaissance architectural style, even though central Europeans built with wattle and daub for thousands of years. Wattle and daub building methods were also developed in Africa, the Americas, and Asia.

Now, there is nothing wrong with assuming that late medieval or Renaissance architectural styles were used in Middle-earth’s most well-known cultures. Tolkien blended a lot of different influences together for each of his cultures. The Rohirrim are a mix of Viking, Greek, and Anglo-Saxon influences, for example. Some people have even argued for a light dusting of Slavic influence in Rohirric culture. So there is plenty of room for wattle and daub architecture in Middle-earth. It’s just not attested in any of Tolkien’s stories.

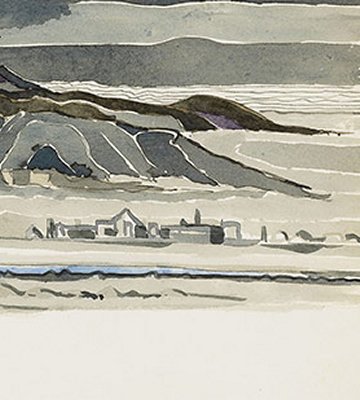

J.R.R. Tolkien drew a few illustrations of the town of Dale, but they were incidental renderings. His attention was focused on Smaug and Erebor. Here is an example of how he illustrated the ruins of dale. His buildings are non-descript and distant. You really cannot determine the architectural style they would have used. In fact, these could be the silhouettes of modern buildings that may have served as inspiration for Tolkien’s artwork. Tolkien’s illustrations seem to imply that a fair number of structures survived. However, after 200 years even stone buildings should have lost their wooden roofs. Some of his other illustrations match that expectation but they provide less detailed form and definition for Dale’s ruins. These illustrations don’t incorporate accurate perspective; he exaggerated perspective, I suppose, to simplify the task of depicting the ruined town. That wasn’t his priority.

So how would I imagine Dale, prior to the coming of the dragon? Well, I imagine there was a wall surrounding the town. Tolkien says there were wars in those days. Thorin and Balin both mentioned the warriors in Dale. And though I have speculated about the size of Dale’s army in the past, it may be significant that Tolkien used the word “warriors” rather than “soldiers”. There are soldiers in Gondor, Riders (knights) in Rohan, and warriors in Dale. Does that mean Dale had a more tribal society, perhaps similar to what we imagine medieval Viking culture to be like? A wall would have been necessary, but it would probably have to be a wooden wall because there is no mention of any ruined wall in the text.

I imagine most of the buildings in the town to be made of wood, perhaps with roofs thatched with straw. A few of the more prominent buildings, perhaps, would have been made of stone. That could account for Tolkien’s representations of large standing buildings. I imagine Girion lived in a large hall, perhaps similar to Meduseld, probably made of stone and timber or stone and turf. Dale was a prosperous town which means it had a mercantile class. That implies there must have been warehouses, workshops, and probably a few other great halls. I also imagine the city surrounded by Viking-style farms. Their buildings would have been made of stone or stone and turf, maybe. I think Tolkien would have meant for the architectural style to be simple and plain as much as possible.

Medieval towers were not always used for defence. Sometimes they were built for status. Dale’s towers could be a mix of functional defensive works and local status homes. They need not have been very tall, only a few storeys at most. Stone towers could have been connected by wooden walls. If Smaug burned the town the walls would not have been rebuilt. After 200 years there would have been nothing left, especially if the dragon occasionally burned down the “desolation” to ensure no one tried to return to the valley.

I don’t think Tolkien would have envisioned Dale to be as elaborate or large as Peter Jackson depicted it in the movies. But I don’t mean that to be a criticism of the movies, either. There is no right way to portray Dale up close and in detail. I think the author meant to leave those details to the reader’s imagination.

# # #

Have you read our other Tolkien and Middle-earth Questions and Answers articles?

Personally, I pictured in my head Dale’s people having a culture similar to the Ainu, Native to Japan and Russia. The use of bells and the crafting of toys, as well as the North-Eastern relative position. Especially, I was reminded of them by Bard, who assimilated into Lake-Town, as many Ainu assimilated into other cultures. Also, he was a great bowman, and Ainu hunters were skilled archers. Finally, I pictured Lake-Town as looking like old Old Town of Lijiang. I know it’s not likely any of these were inspirations for Tolkien, but it always matched in my head.

“A wall would have been necessary, but it would probably have to be a wooden wall because there is no mention of any ruined wall in the text.”

“…and gazing out from it over the narrow water, foaming and splashing among many boulders, they could see in the wide valley shadowed by the Mountain’s arms the grey ruins of ancient houses, towers, and [b]walls[/b].”

Yes. What I should have written was “no explicit mention of any ruined city wall in the text”, as the quoted text doesn’t say what the walls were used for.

Given that “walls” in other contexts of Tolkien usually seem to refer to fortification walls, I think there’s a presumption one could rest on that Tolkien means that here, too. Likewise, a house or a tower that is at all intact necessarily has walls of its own – a singling out of walls by name would point to structures which are walls in entirety.

For these reasons, I had always taken this passage to refer to the remains of fortification walls – walls almost certainly stone or brick, given the age, wealth, and proximity of Dale to the Dwarven engineers of Erebor before its ruin. Perhaps not stone walls to compare with those of Gondor in its glory, but sturdy enough to compare with that of a fairly prosperous Roman or late medieval town with reasonable access to stone.

None of which is a mathematical certainty, of course. But I think it’s at least a rebuttable presumption.

My imaginings come somewhere between yours and Peter Jackson’s. I seriously doubt Dale would have been as travelogue-perfect as Rothenburg. Real world municipalities have to be a bit more gritty and utilitarian – Monty Python and the Holy Grail rather than Walt Disney’s Snow White.

Certainly a town named Dale can’t occupy a fortified hilltop as Jackson’s version does. But I think the town in its heyday was larger and more prosperous than you suggest. It was clearly the principal center for trade in that portion of Middle-earth; the commercial gateway for Erebor. It would have to outstrip Lake Town by a substantial margin, as the regional economy just couldn’t return to past glories without The Lonely Mountain.

To me, the town center would undoubtedly be all masonry, reflecting prosperity and the ready availability of excellent dwarvish stoneworkers. It’s also hard to have an extensive, 200-year-old ruin if the community had been predominantly stick-built. Wood construction would more likely be found in the poorer, surrounding residential quarters. Tolkien’s drawings likely represent only what survived the dragon fire – a sizable stone-built town center.

Still, my imaginings don’t leave room for highly ornamented stonework. I picture the kind of sturdy, utilitarian stonework we find throughout Northern Europe, rather than a mini-Minas Tirith. The goal wasn’t to impress; durability was the top priority, both for the sake of the ages and to escape the occasional man-made conflagration (see: Cow, Mrs. O’Leary’s). Not to say that dragon-proofing was on their minds – no doubt the roofing and flooring would have been timber and some rooms would be wood paneled. Roofs would be steeply pitched to shed the snows that fall in northern climes. I’d like to think they’d have invested in stone roofing tiles, but if that practice had been widespread, Smaug might had a harder time laying waste. While thatch is not unheard of for stone buildings, I think it’d be too down-market for prosperous merchants. Thick, wood shingles would be the perfect compromise – lower maintenance than thatch, readily ignited with a single blast of dragon fire.

The reference to ‘grey ruins’ certainly means stone. And vonsidering that Dwarves would be fairly influential in development of this city I picture it as stone made structures, grand architecture of greater sophistication (maybe not quite the numenorean but still). Presence of towers also suggests lots of stonework. Dwarves would have taught the Men much about masonry and building, and what they would not teach, the Dwarves would have build on order of the inhabitants. Lords of Dale would certainly use dwarven services in construction of their city (and it is plainly written in texts that Dwarves in allying with Men offered their services in building roads, bridges, fortified dwellings), it’s streets and walls/fortification would be rather advanced by dwarven art and craft.

In numenorean realms even smaller towns and settlements like Bree had large stone houses, so masonry along with easily available stone from dwarven mines and quarries, would be the obvious for local Men to use in establishing Dale. Also it might be that Dale already back then had smaller villages and settlements about.

In fact it is suggested as such in The Hobbit:

“Moreover I am by right descent the heir of Girion of Dale, and in your hoard is mingled much of the wealth of his halls and towns, which old Smaug stole.”

‘Towns’ in plural is used, and the fertility of the valley certainly means lots of farms around (and after rebuilding the valley is specifically said to be tilled again and plentiful in yielding crops).