Q: What Was J.R.R. Tolkien’s Inspiration for Lake-town in The Hobbit?

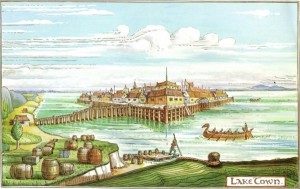

ANSWER: Many readers have compared Tolkien’s Lake-town to Venice, especially pointing out the similarity between the Masters of Lake-town — who were elected to their positions “from among the old and the wise” — and the Doges of Venice, who were elected to their offices for life from among the leading merchant families. The Venetian Doges were not paid much so they maintained their trading businesses, much like the Master of Lake-town, who thought of “trade and tolls … cargoes and gold, to which habit he owed his position.”

Venice, of course, was built on several small islands in a lagoon in northeastern Italy. Although there were always “lagoon dwellers” in the region, many Romans fled from nearby cities to seek refuge in the lagoon from the incursions of the Huns and Lombards, who attacked Italy in the 5th and 6th centuries CE.

Other people have noted the similarity in character between the Master of Lake-town and the Mayor of Hamelin in the story of the Pied Piper. Both men are conniving and greedy, and they make bad decisions. But while Tolkien may have had Hamelin’s fictional mayor in mind, it’s unlikely he found much helpful inspiration in other parts of the story.

Most readers are also probably aware of the comparison between Lake-town and the Neolithic lake villages of Switzerland. What most readers may not realize, however, is that these lake villages are found throughout Europe, and that Tolkien may very well have been aware of their extent and theoretical history. In 1921 American anthropologist John Mason Tyler published a book titled The New Stone Age in Northern Europe. The book received considerable attention in scholarly circles in 1921 and 1922. It has been cited in several works since then, although recent research appears to challenge a number of Tyler’s interpretations. Still, in the 1920s and 1930s J.R.R. Tolkien would have had ample opportunity to become aware of and influenced by Tyler’s book. Here are a few citations for comparison:

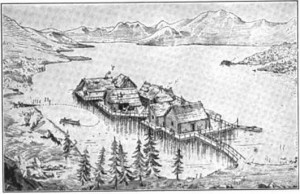

Not far from the mouth of the Forest River was the strange town he heard the elves speak of in the king’s cellars. It was not built on the shore, though there were a few huts and buildings there, but right out on the surface of the lake, protected from the swirl of the entering river by a promontory of rock which formed a calm bay. A great bridge made of wood ran out to where on huge piles made of forest trees was built a busy wooden town, not a town of elves but of Men, who still dared to dwell here under the shadow of the distant dragon-mountain. They still throve on the trade that came up the great river from the South and was carted past the falls to their town; but in the great days of old, when Dale in the North was rich and prosperous, they had been wealthy and powerful, and there had been fleets of boats on the waters, and some were filled with gold and some with warriors in armour, and there had been wars and deeds which were now only a legend. The rotting piles of a greater town could still be seen along the shores when the waters sank in a drought.

This introduction to Lake-town provides a rather detailed basis for comparison in relatively few words. The piles were made from “forest trees” and the town “throne on the trade that cam up the great river” and “the rotting piles of a greater town could still be seen along the shores when the waters sank in a drought”. This latter statement is most telling, for that is precisely the type of event that Tyler describes at the beginning of his chapter on Lake Dwellings:

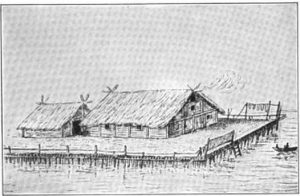

The winter of 1853-1854 was exceedingly cold and dry. The surface of the Swiss lakes sank lower than at any time during many preceding centuries. The lowering of the water tempted the inhabitants along the shore to erect dikes and thus fill in the newly gained flats. During this process the workmen along the edge of the retreating water came upon the tops of piles, and between those great quantities of horn and stone implements and fragments of pottery. Aeppli, a teacher in Obermeilen, called the attention of the Antiquarian Society in Zurich to these discoveries. The society recognized at once their importance, and under the leadership of its president, Ferdinand Keller, began a series of most careful investigations which have contributed more to our knowledge of life during the Neolithic period than any discoveries before or since.

The number of these lake-dwellings is very large. Lake Neuchatel has furnished over 50; Lake Leman (Geneva) 40; Lake Constance over 40; Lake Zurich 10. The shores of the smaller lakes have also contributed their full quota. In some of the lakes where the shore was favorable, remains of a lake-dwelling have been found before almost every modern village. Sometimes we find the remains of two villages, one somewhat farther out than the other. In these cases the one nearer the shore is the older, usually Neolithic, while the one farther out belongs to the Bronze period.

These settlements are by no means limited to Switzerland. They stretch in a long zone along the Alps from Savoy and southern Germany through Switzerland into Austria. Herodotus mentions them in the Balkan Peninsula. The amount of bronze seems to increase as we pass from east to west. They are found frequently in the Italian lakes, mostly containing relics of the Bronze Age, though here the western settlements contain little or no metal. A second series has been discovered in Britain and northern Germany, and extending into Russia. These are considerably younger. The scheme of the lake-dwelling was used in historic times in Ravenna and Venice. Large numbers are still inhabited in the far east.

So here again we are drawn to Venice, which is included in the list of numerous locations for these lake villages. According to Tyler they were common and often rebuilt, just as Lake-town has been rebuilt at least once. The inhabitants of these prehistorical villages have not been identified. They are not Celts or Germans, as those peoples did not emerge from Europe’s various cultures until much later. The motif is broad and generic enough that it feels reasonably “real” in fiction, even in The Hobbit, which is “just a children’s story”. But Lake-town is unique in Tolkien’s fiction because — except for the bridges of Tharbad and Osgiliath — he does not appear to devise any other water-top habitats for either Elves or Men. The description of Lake-town in The Hobbit probably resembles medieval Venice more than some prehistoric village, however.

“Follow me then,” said the captain, and with six men about them he led them over the bridge through the gates and into the market-place of the town. This was a wide circle of quiet water surrounded by the tall piles on which were built the greater houses, and by long wooden quays with many steps and ladders going down to the surface of the lake. From one great hall shone many lights and there came the sound of many voices. They passed its doors and stood blinking in the light looking at long tables filled with folk.

The comparison to Venice is even more apropos a little further one, where Tolkien writes:

Soon afterwards the other dwarves were brought into the town amid scenes of astonishing enthusiasm. They were all doctored and fed and housed and pampered in the most delightful and satisfactory fashion. A large house was given up to Thorin and his company; boats and rowers were put at their service; and crowds sat outside and sang songs all day, or cheered if any dwarf showed so much as his nose.

Why would the Dwarves need boats and rowers if they could simply move around Lake-town on the wooden walkways?

In looking at Tolkien’s own illustrations of Lake-town, it’s obviously not closely modeled on a Neolithic village. The buildings are of a more modern design, and could have been built from the Middle Ages onward. There are towers, spires, arches, chimneys, and other architectural features that were developed only thousands of years after the Neolithic lake dwellings of Europe were built. An interesting passage from Tyler’s chapter cannot help but strike a chord with Tolkien’s readers, though, for Lake-town is destroyed by Smaug’s fire and the people of the town face starvation if they do not receive help from the Elven-folk of Mirkwood.

A lake-dwelling of any size is inconceivable without a well-advanced social development. It could hardly be founded, builded, or maintained without close co-operation. Families had to live closely crowded together, almost as in our modern cities. Neighbors had learned to get on with one another and live together in peace, and to submit to a close regulation or discipline by law or custom. They seem to have been a peaceful folk and exposed to no great dangers from outside attack, at least in Neolithic time. When the ice fringed the shores or covered the small lakes, they must have been easily open to attack. A few brands thrown into the thatched roof would have brought sure destruction. Traces of conflagration occur, as at Robenhausen, which was twice destroyed by fire.1 But these occurrences are rare. Neolithic settlements seem to have been more frequently abandoned because of the growth of peat than by any sudden or violent destruction. Conditions probably changed in this respect during the Bronze period.

Their food was varied and more than fairly abundant. They had their domestic animals to furnish flesh, milk, probably butter and cheese. Agriculture was primitive, but in some cases we find large stores, we might say granaries, of wheat; and wild fruits and vegetable foods were abundant. The forests offered game, and the lakes were well-stocked with fish. There may have been times of hardship and dearth, but famine could hardly have ravaged a people with these three sources of supply.

The lake offered a thoroughfare for their canoes, and communication was easy for long distances. To cite only one illustration: flint was brought from Grand Pressigny, in France, and manufactured in certain Swiss localities. There was much variety and division of labor between different villages. One manufactured flint very largely – so at and around Moosseedorf; while Robenhausen and Wangen have furnished great quantities of cloth. Others were rather centres for the manufacture of pottery. Even in the same village one area is richer in one product, a second in another. There was much variety as well as freedom of intercommunication. The whole region lay a little back from the great Danube thoroughfare, but near enough to it to retain connection with the larger world. Life was not altogether monotonous.

In fact, in The Hobbit the narrator points out that the people of Lake-town have not lost as much as they at first believe, when Smaug has just died:

Full on the town he fell. His last throes splintered it to sparks and gledes. The lake roared in. A vast steam leaped up, white in the sudden dark under the moon. There was a hiss, a gushing whirl, and then silence. And that was the end of Smaug and Esgaroth, but not of Bard. The waxing moon rose higher and higher and the wind grew loud and cold. It twisted the white fog into bending pillars and hurrying clouds and drove it off to the West to scatter in tattered shreds over the marshes before Mirkwood. Then the many boats could be seen dotted dark on the surface of the lake, and down the wind came the voices of the people of Esgaroth lamenting their lost town and goods and ruined houses. But they had really much to be thankful for, had they thought of it, though it could hardly be expected that they should just then: three quarters of the people of the town had at least escaped alive; their woods and fields and pastures and cattle and most of their boats remained undamaged; and the dragon was dead. What that meant they had not yet realized.

It would seem upon reflection that Lake-town is a careful blending of resources easily available to Tolkien. He knew the story of the Pied Piper but there are doubtless other tales of miserly mayors and towns ruled by business leaders. The history of Venice and its elected Doges was well-documented; and even the prehistoric lake villages of Europe had been well-studied for many years and given careful consideration in the scholarly literature of the day. It seems unlikely there was any one source of inspiration for Lake-town and its people, but rather several — and perhaps even some that have not yet come to light.

# # #

Have you read our other Tolkien and Middle-earth Questions and Answers articles?

[…] many years. Tolkien has been quoted as comparing Gondor to Venice (Letter No. 168 — also, Cf. What was J.R.R. Tolkien’s Inspiration for Lake Town in The Hobbit?). The Barbary Corsairs usually operated in fleets rather than by lone ships (as was common among […]