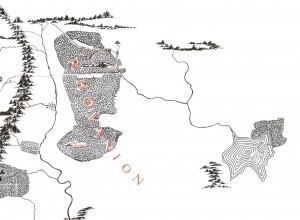

Q: Where Did the Old Forest Road in Mirkwood Lead To?

ANSWER: J.R.R. Tolkien does not seem to have written much about the history of the Old Forest Road, which first appeared in The Hobbit. Beorn advised Thorin and Company not to use the road to try to reach Erebor because it had by this time (Third Age year 2941) fallen into disuse, except by goblins (orcs). The eastern end of the road vanished into marshes on the edge of the forest.

In a note attached to the essay “Of Dwarves and Men” (published in The Peoples of Middle-earth, Volume XII of The History of Middle-earth), J.R.R. Tolkien wrote:

30. For a time. The Numenoreans had not yet appeared on the shores of Middle-earth, and the foundations of the Barad-dur had not yet been built. It was a brief period in the dark annals of the Second Age, yet for many lives of Men the Longbeards controlled the Ered Mithrin, Erebor, and the Iron Hills, and all the east side of the Misty Mountains as far as the confines of Lorien; while the Men of the North dwelt in all the adjacent lands as far south as the Great Dwarf Road that cut through the Forest (the Old Forest Road was its ruinous remains in the Third Age) and then went North-east to the Iron Hills. [As with so much else in this account, the origin of the Old Forest Road in ‘the Great Dwarf Road’, which after traversing Greenwood the Great led to the Iron Hills, has never been met before.]

The text to which this note was attached reads thus:

The Men with whom they were thus associated were for the most part akin in race and language with the tall and mostly fair-haired people of the ‘House of Hador’, the most renowned and numerous of the Edain, who were allied with the Eldar in the War of the Jewels. These Men, it seems, had come westward until faced by the Great Greenwood, and then had divided: some reaching the Anduin and passing thence northward up the Vales; some passing between the north-eaves of the Wood and the Ered Mithrin. Only a small part of this people, already very numerous and divided into many tribes, had then passed on into Eriador and so come at last to Beleriand. They were brave and loyal folk, truehearted, haters of Morgoth and his servants; and at first had regarded the Dwarves askance, fearing that they were under the Shadow (as they said).28 But they were glad of the alliance, for they were more vulnerable to the attacks of the Orks: they dwelt largely in scattered homesteads and villages, and if they drew together into small townships they were poorly defended, at best by dikes and wooden fences. Also they were lightly armed, chiefly with bows, for they had little metal and the few smiths among them had no great skill. These things the Dwarves amended in return for one great service that Men could offer. They were tamers of beasts and had learned the mastery of horses, and many were skilled and fearless riders.29 These would often ride far afield as scouts and keep watch on movements of their enemies; and if the Orks dared to assemble in the open for some great raid, they would gather great force of horsed archers to surround them and destroy them. In these ways the Alliance of Dwarves and Men in the North came early in the Second Age to command great strength, swift in attack and valiant and well-protected in defence, and there grew up in that region between Dwarves and Men sometimes warm friendship.

It was at that time, when the Dwarves were associated with Men both in war and in the ordering of the lands that they had secured,30 that the Longbeards adopted the speech of Men for communication with them….

The old road is also mentioned in Note 14 attached to “The Disaster of the Gladden Fields”, which was published in Unfinished Tales of Numenor and Middle-earth:

14 Long before the War of the Alliance, Oropher, King of the Silvan Elves east of Anduin, being disturbed by rumours of the rising power of Sauron, had left their ancient dwellings about Amon Lanc, across the river from their kin in Lórien. Three times he had moved northwards, and at the end of the Second Age he dwelt in the western glens of the Emyn Duir, and his numerous people lived and roamed in the woods and vales westward as far as Anduin, north of the ancient Dwarf-Road (Men-i-Naugrim). He had joined the Alliance, but was slain in the assault upon the Gates of Mordor. Thranduil his son had returned with the remnant of the army of the Silvan Elves in the year before Isildur’s march.

The Emyn Duir (Dark Mountains) were a group of high hills in the north-east of the Forest, so called because dense fir-woods grew upon their slopes; but they were not yet of evil name. In later days when the shadow of Sauron spread through Greenwood the Great, and changed its name from Eryn Galen to Taur-nu-Fuin (translated Mirkwood), the Emyn Duir became a haunt of many of his most evil creatures, and were called Emyn-nu-Fuin, the Mountains of Mirkwood. [Author’s note.] – On Oropher see Appendix B to “The History of Galadriel and Celeborn;” in one of the passages there cited Oropher’s retreat northwards within the Greenwood is ascribed to his desire to move out of range of the Dwarves of Khazad-dûm and of Celeborn and Galadriel in Lórien.

The Elvish names of the Mountains of Mirkwood are not found elsewhere. In Appendix F (II) to The Lord of the Rings the Elvish name of Mirkwood is Taur-e-Ndaedelos “forest of the great fear;” the name given here, Taur-nu-Fuin “forest under night,” was the later name of Dorthonion, the forested highland on the northern borders of Beleriand in the Elder Days. The application of the same name, Taur-nu-Fuin, to both Mirkwood and Dorthonion is notable, in the light of the close relation of my father’s pictures of them: see Pictures by J.R.R.Tolkien, 1979, note to no.37. – After the end of the War of the Ring Thranduil and Celeborn renamed Mirkwood once more, calling it Eryn Lasgalen, the Wood of Greenleaves (Appendix B to The Lord of the Rings).

Men-i-Naugrim, the Dwarf Road, is the Old Forest Road described in The Hobbit, Chapter 7. In the earlier draft of this section of the present narrative there is a note referring to “the ancient Forest Road that led down from the Pass of Imladris and crossed Anduin by a bridge (that had been enlarged and strengthened for the passage of the armies of the Alliance), and so over the eastern valley into the Greenwood. The Anduin could not be bridged at any lower point; for a few miles below the Forest Road the land fell steeply and the river became very swift, until it reached the great basin of the Gladden Fields. Beyond the Fields it quickened again, and was then a great flood fed by many streams, of which the names are forgotten save those of the larger: the Gladden (Sîr Ninglor), Silverlode (Celebrant), and Limlight (Limlaith).” In The Hobbit the Forest Road traversed the great river by the Old Ford and there is no mention of there having once been a bridge at the crossing.

Christopher Tolkien suggests that “The Disaster of the Gladden Fields” belongs with the last work on Middle-earth his father engaged in, sometime in the mid- to late 1960s and early 1970s. I have accordingly presented such information here as I have available in the order in which it was composed.

What we can infer from these texts is that the road was clearly used for commerce in Tolkien’s imagination “at some time in the past”. Thorin’s familiarity with the road seems to imply that Tolkien meant — at the time he wrote The Hobbit — for the Dwarves to have known about it, if not necessarily to have used it in their youth. Nonetheless, years later while working on The Lord of the Rings and subsequent texts he seems to have given thought to a reasonable purpose for the road that would be consistent with the stories he had told. Hence, it became the Men-i-Naugrim and had once been used by the Dwarves (and perhaps Men) to maintain communication across the far-flung territories controlled by and/or allied with the Longbeard Dwarves in the Second Age.

The insertion of the bridge into the road’s history does not contradict anything published in The Hobbit. Presumably the bridge would have fallen into disuse and ruin after the political disruptions of the North. The road (and bridge) may have been maintained until about Third Age year 1981, when the Dwarves of Khazad-dum fled their ancient home, driven away by the Balrog. After that time the Dwarves of the Iron Hills (and later Erebor) might have still had a use for the road to maintain contact with the Dwarves of the Ered Luin. Sauron retreated from Mirkwood in Third Age year 2063 and the Forest had peace for a few centuries after that time.

However, it could be that the road fell into disuse around the time of Third Age year 1851. That was the year that the ancient “Kingdom of Rhovanion” was conquered by the Wainriders. The Northmen of Rhovanion made their homes in the East Bight, the former heavily wooded region on the east side of Mirkwood, and south of where the old road reached Celduin. While the Northmen controlled that region the old road was probably relatively safe. But after Rhovanion was overthrown none of the Free Peoples ever again re-established a realm in that area. There is a brief mention in Unfinished Tales of Numenor and Middle-earth of the Wainriders slaying and driving north along the Celduin Men who had been friendly to Rhovanion’s people.

So while we cannot say there was a town at the location where the road met the river there was certainly opportunity for a town to arise there. Travelers would have crossed the river by boat, and it would make sense to maintain some sort of outpost near the road’s eastern end simply for the sake of maintenance and security. The Northmen of Rhovanion could have traveled north by land or by river. Certainly the inhabitants of Dorwinion (thought by many to be Elves, perhaps Avari or Silvan Elves) seem to have used the river for commerce.

Such a town, if it existed, could have resisted the incursions of the Wainriders and their successors, the Balchoth, for a while. The reference in “Cirion and Eorl” places the time of flight north up the river in Cirion’s early reign, circa Third Age year 2489. This would have been centuries after the destruction of both Rhovanion and Khazad-dum. Any town of Northmen left in the area would have had little economic base to support a large population and army. These are speculations that fit facts which allow for speculations, so about all we can say is that if you want to write fan fiction or design a role-playing module that takes your players through this area these are some ideas to consider.

# # #

See also:

- Why Did Sauron Need a Road from Barad-dur to Sammath Naur?

- Why Did the Fellowship Not Take any Maps with Them?

- Where Did Boromir Die in The Lord of the Rings?

- How Many Roads Led Into the Shire?

- Why are There So Few Roads in Middle-earth?

- Do the Rohirrim of Rohan Use Boats?

Have you read our other Tolkien and Middle-earth Questions and Answers articles?

If the Old Forest Road was closed; then what road did the Dwarves take when they did business between the Ered Luin and thier eastern realms? Did they use the Elf-path that Thorin & Company took? Or did they go around Mirkwood in the north?

Since Bilbo, Gandalf, and Beorn traveled around the northern end of the forest on their return journey I would guess that would have been a relatively safe route for the Dwarves when traveling between the Iron Hills and the west.

At Rivendell Gimli says “if it were not for the Beornings, the passage from Dale to Rivendell would have long ago become impossible. They are valiant men and keep open the High Pass and the ford of Carrock. But their tolls are high…” This certainly allows the possibility that the route is via the Carrock and the elf-path, which would in any case be the most direct one, with the Old Forest Road and its ford still disused.

Incidentally, although the Carrock is shown as an island on both maps, the description in The Hobbit does not quite suggest this: “cropping out of the ground, right in the path of the stream which looped itself about it, was a great rock, almost a hill of stone…” The only ford mentioned is the one that leads from the Carrock itself to the eastern bank. I wonder if Karen Fonstad had anything to say about it?

There were two Carrocks if I recall correctly, although I don’t recall which one is in The Hobbit. I think Fonstad had something to say about this but my copy of her book is packed up somewhere. I may try to dig it up later and see what I can find.

I suppose it doesn’t add much to the study to mention this, but it’s still perhaps worth mentioning that the idea of this Dwarf-road is clearly recycled from the Dwarf-road in Beleriand. (Just as this Taur-nu-Fuin is recycled from the Taur-nu-Fuin north of Beleriand, complete with Necromancer, albeit with Doriath tacked on.)

I think there is definitely a connection to the Beleriand Dwarf-road, in that early versions of the story appear to have been more strongly tied to the Beleriand stories and possibly even the landscape. But clearly Tolkien tried to make the road more relevant and meaningful in later years.